Wolfgang Burat at Habib University (Karachi 2018)

Is this your first time in Pakistan?

Yes, it’s my first time in Pakistan.

How do you like it?

I like Pakistan very much and what I like has more to do with how I see people getting along with each other than with what they get along with. Pakistan is very chaotic and chaos is the future. If I get back to Germany, I’ll die of boredom.

Well, that implies that Pakistan is the future, doesn’t it?

Absolutely. Karachi is chaotic, but I have a feeling that this is a kind of future global thing. Pakistanis learn very well how to cope and get along with chaos, and I admire the people for their getting along.

When did you start with photography? What sparked your interest in that medium?

I don’t remember. I was very young, twelve years or so. I wanted to become a pilot, but then I realized that I couldn’t become a pilot because I had a problem with my back. So, I decided to become a photographer.

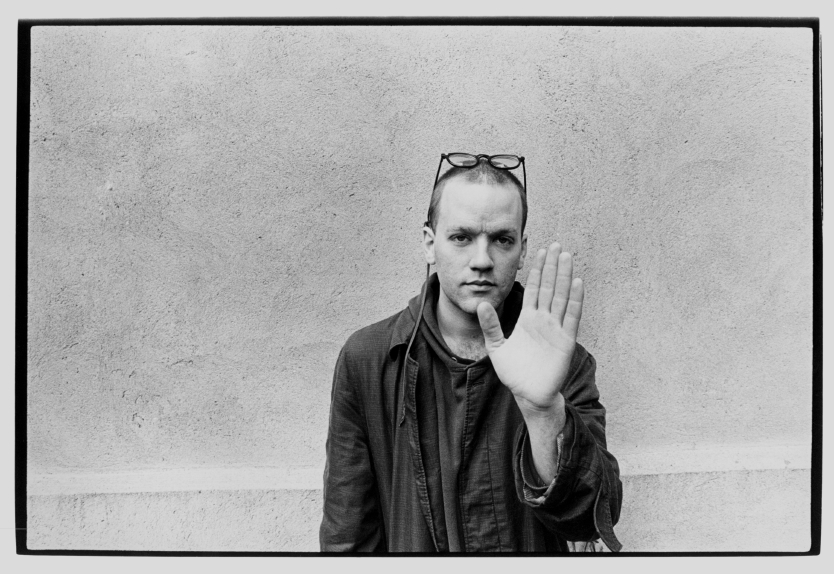

Self-Portrait (Cologne 1982) © Wolfgang Burat

Why photography?

I don’t remember why. I found it interesting to work with technical things and I had an affection for pictures and framing, but I don’t exactly remember this.

What did you start photographing with?

I started photographing with my family, flowers in the garden, dogs, miniature trains and things like that.

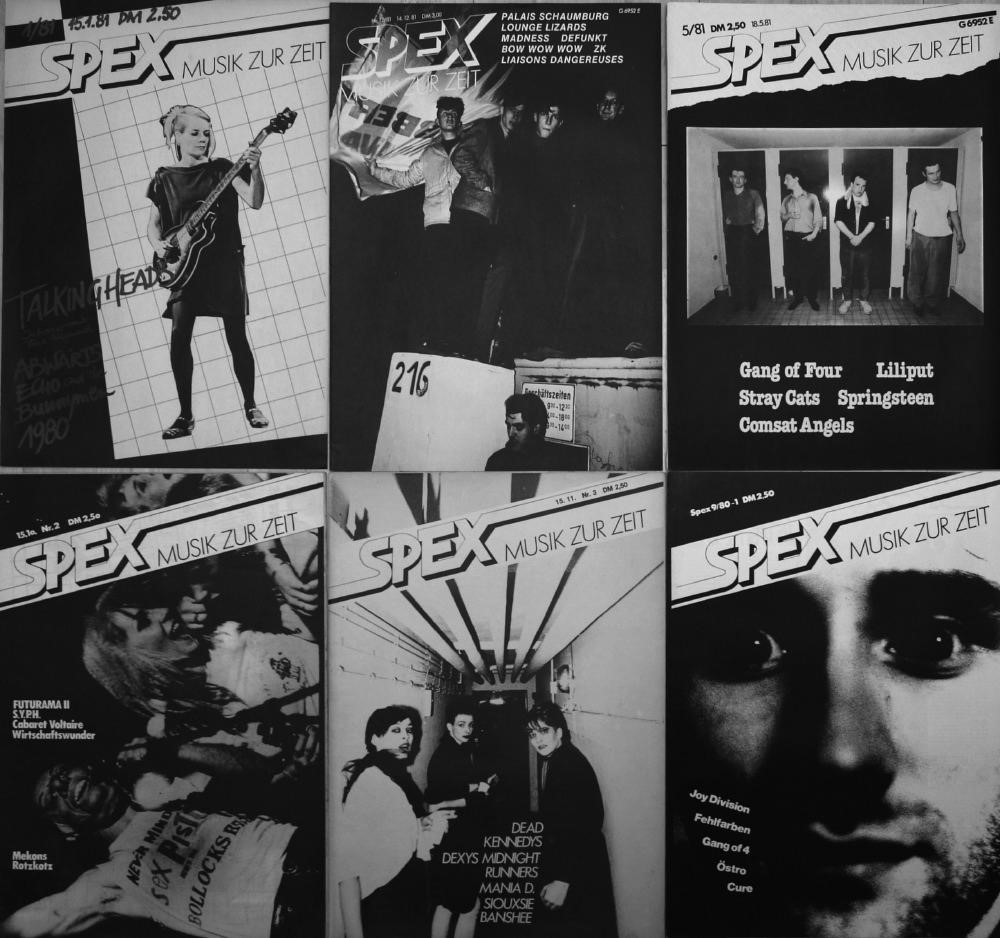

You were studying photographic engineering at the University of Applied Sciences in Cologne when the music magazine Spex was founded. How did you become a part of Spex?

Peter Bömmels, the brainchild behind Spex – now a successful painter and an art professor – was my neighbor. He was working in a kindergarten and was studying social pedagogy. One day he approached me and said: “What do you think about making a magazine? Let’s get some people on board.” We gathered in a bar, talked it over and so it began.

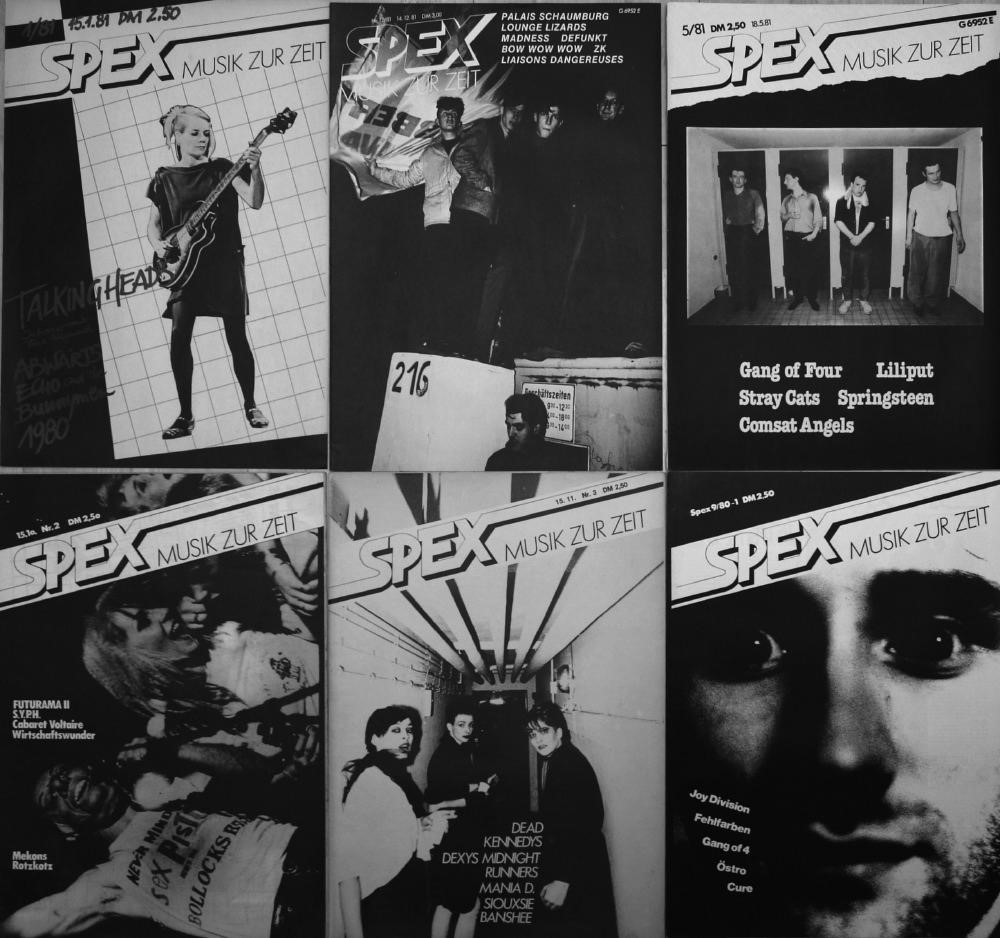

Spex magazine’s early covers with photographs by Wolfgang Burat © Wolfgang Burat

What was it about Spex that attracted you?

I could work on stuff I was interested in like music and aspects pertaining to culture and youth, but mainly music.

Was the idea behind Spex to create a music magazine that was different?

Yes, the main idea was to create a different magazine because the popular magazines stuck to hippie and rock and at the time punk and new wave came up. Punk was totally different, but there was no forum or magazine. So, that was the idea.

The name Spex comes from spectacles/specs. So, I guess the idea was to develop and/or have a certain view or perspective. What perspective did Spex have?

Yes, the idea was to have a special outlook on things, but the title also had to do with a new wave band called X-Ray Spex – the idea of an X-ray specs which allowed an individual to see through and behind things.

Spex magazine’s editors and publishers (Cologne 1984) © Wolfgang Burat

So, it was about seeing things differently?

Absolutely, it was about seeing things differently. We were not working on seeing things differently, we just saw things differently and wanted to create a forum.

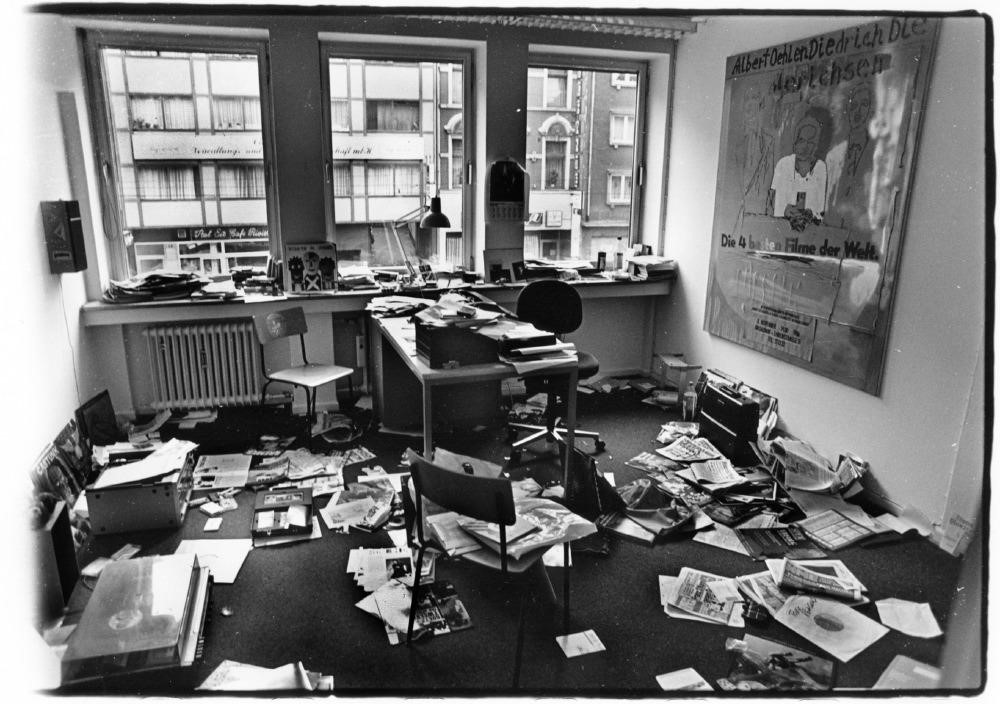

You were one of the publisher-groups of Spex until 1990. Can you walk us through the process of publishing an issue of Spex back in the early 80s?

It was an analog process. Making an analog magazine meant that texts had to be written and photographs had to be developed. The texts and photographs were then printed out and glued together according to layout and templates for ads. These collages were then reproduced photographically and transferred to a printing machine. The printing process was totally analog.

How is it different today?

The distribution process is the same, but the production process is totally different. Today, you have a digital workflow which is totally different from an analog workflow.

Self-Portrait (Cologne 2014) © Wolfgang Burat

Your archive comprises numerous black and white prints produced between 1980 and 1990. What’s the deal with the black and white prints?

The black and white prints were cheaper and I could easily produce them myself. I had a dark room where I produced all the photographs firsthand. It was cheap to process black and white prints. I developed films, produced prints and put them on paper; I could control the technical process myself. The colored prints were very complicated and involved a lot of chemical workout, whereas the black and white prints were much easier to handle.

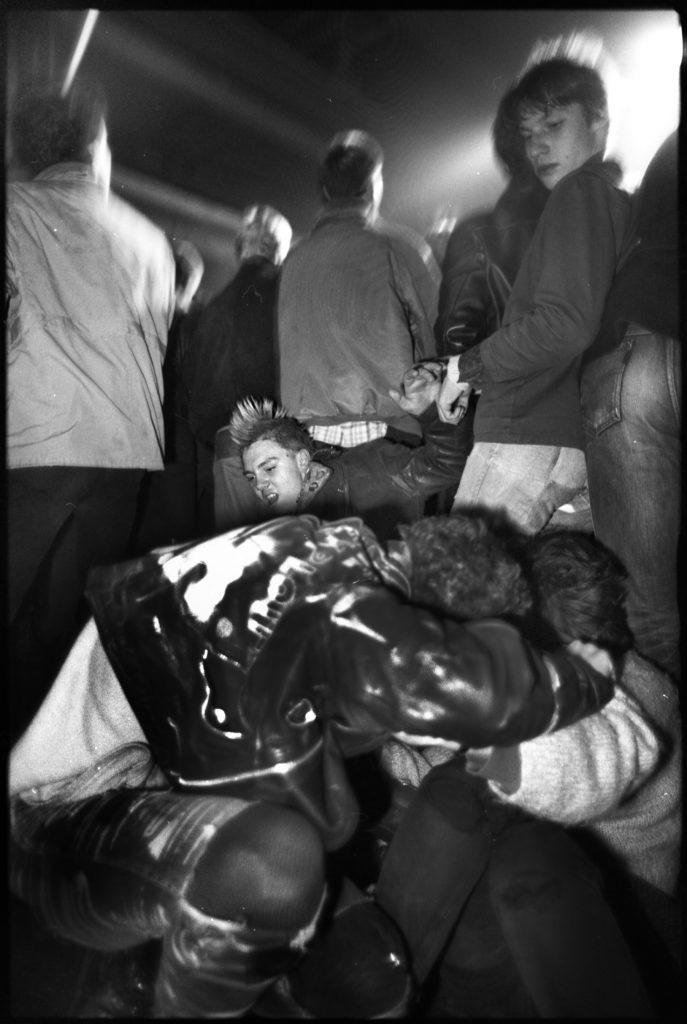

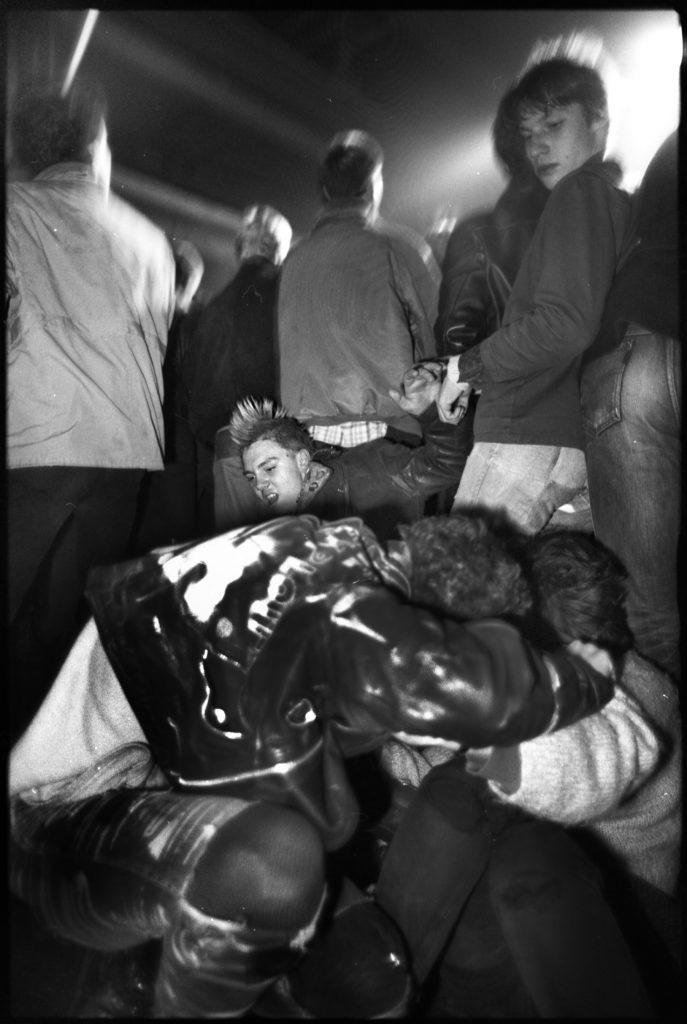

“Pogo” (Black Flag Concert, Köln 1983) © Wolfgang Burat

You photographed artists, backstage situations, bands, fans, live gigs and musicians back in the 80s. What were you photographing before the 80s?

Before the 1980s, I was a student and was not working as a professional photographer. I did music photography for a small record label. I took cover photographs for singers and bands signed by unpopular small record labels. So, I was already a bit in contact with music. Spex was more or less my first professional job. I came to music through Spex because we were writing about music; I was twenty-four and very much into music. I would listen to music all day long from morning till evening. So, the music connection was just there.

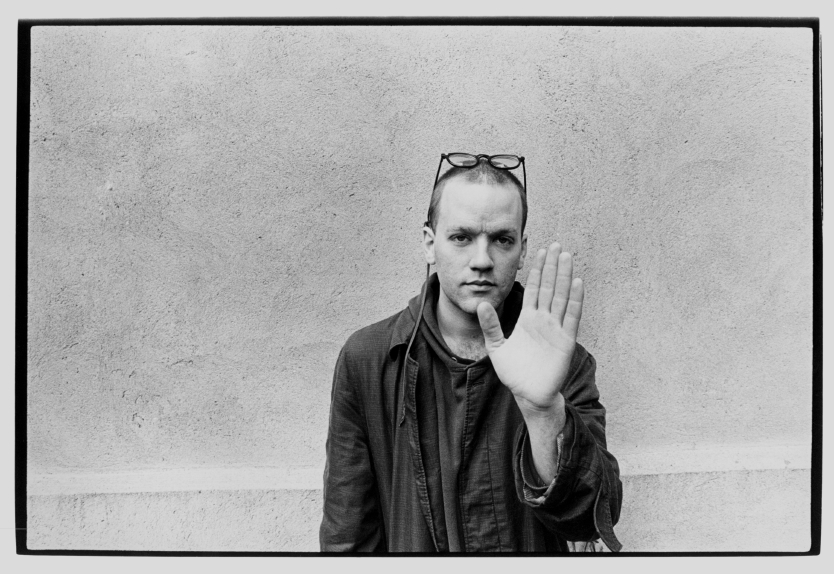

Michael Stipe (Cologne 1985) © Wolfgang Burat

What did you have in mind when you took a photograph?

The first thing I had in mind was to take a photograph that was printable and interesting. In terms of product, to produce a product that was usable, but I wanted to have a unique photograph unlike other photographs.

During the 80s, you printed photographs in your own laboratory. How has technology influenced your technique? How has your technique evolved over the years?

The influence has always been the same. You have to learn the techniques and handle them. I personalized the techniques. Whether analog or digital, I have my personal way to use the techniques. I don’t do it on a general basis or how it is done in brackets. I explored the techniques my way by looking at how I could handle them myself.

You were studying photographic engineering. Did your education influence your style?

It’s hard to say. I always had a big problem with studying engineering because I saw it was not what I really wanted (laughs). I was very happy to work creatively.

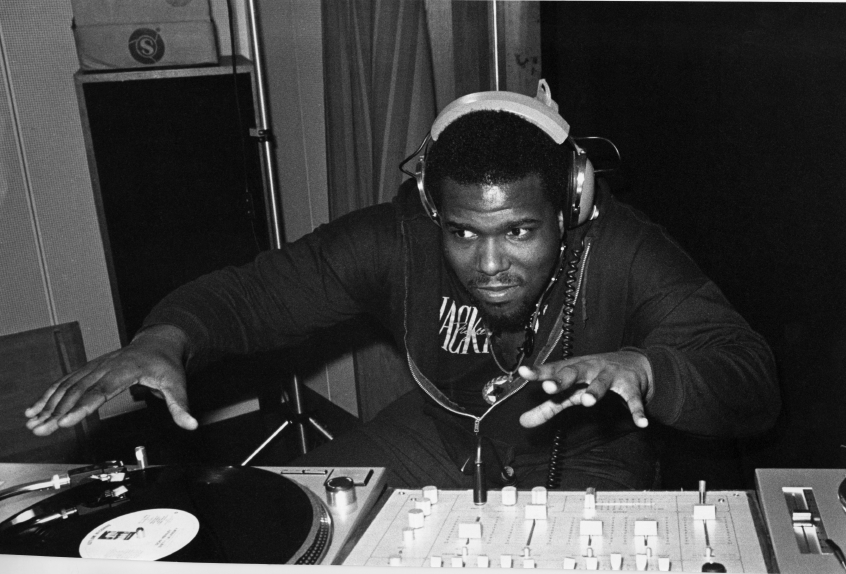

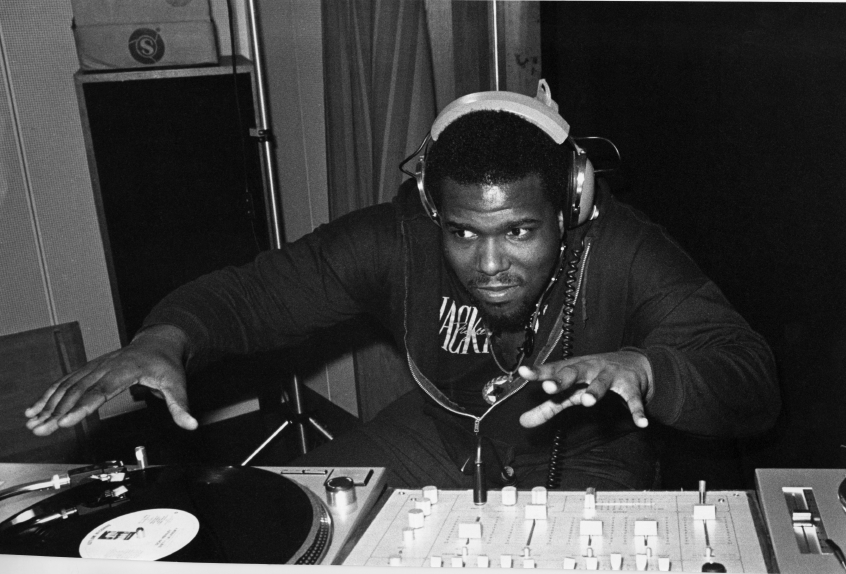

Afrika Bambaataa (Cologne 1983) © Wolfgang Burat

Isn’t photographic engineering about photography?

Yes, it’s about photography, but photographic engineering means that you work for the photographic industry which at the time comprised both the chemical industry and the optical industry. Today, what is left of the photographic industry is the optical industry. The rest has disappeared. So, what I studied in a way is like the steam machine techniques. I’m a steam machine engineer (laughs).

Which genre of photography would you associate yourself with and has it changed over time?

Yes and no. The genre I’m into – music photography – has changed a lot because of how the society has changed. The outlook on media and the consciousness of media has totally changed. In the early 80s, people had another conscience pertaining to media existence. Today, media existence has fully grabbed the people and their perception. This is the difference. For example, you can’t go to a concert and just take photographs because someone can come and tell you that photographing is not allowed.

But today anyone can become a photographer, for example, iPhone photography.

That’s also true, of course. Anyway, at the time, you could take photographs and noone would give a damn. Today, you can do the first three pieces of music, take photographs from the ditch in front of the stage at big concerts. This didn’t exist before. Also, the managing department of artists wants to control the media image of their artists. This has also changed. Back then, the artists were contacted by other artists. These artists were journalists and photographers and so on, but not media workers. Today, journalists and musicians are media workers. This is the difference.

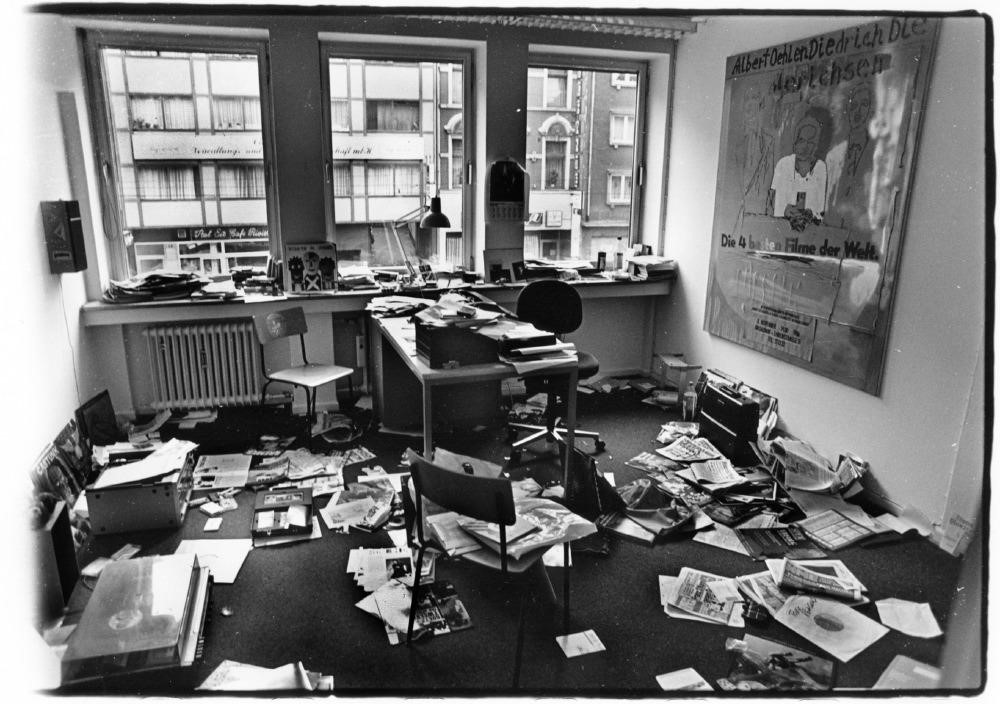

Office of Spex magazine’s Chief-Editor Diedrich Diederichsen (Cologne 1987) © Wolfgang Burat

Maybe Adorno was right about the ‘culture industry’. He was just ahead of his time with that idea. Do you miss the 80s?

No, I don’t miss them.

No tears!

(laughs) Yeah, right. But I’m very happy that they are part of my history. I’m a half-and-half person. I’m half analog and half digital. This gives me a very nice possibility of combining things. When I see a digital product, I can remember the analog product. I have another relation to it … another understanding of what might be an image or a sound or a light or whatever. This is a very big field and I could talk a lot about it. I think you are studying it here and this is something you as media students should really be aware of.

Mark E. Smith (1985) © Wolfgang Burat

Analog or Digital? Which do you prefer?

I have no preferences here. I don’t want to decide between the two. And I don’t have to.

Like Melville’s Bartleby: ‘I would prefer not to.’

Exactly. It’s about options. Digital is good because it’s so fast and you can come to your aim very fast. Analog is good because you can create more unique things like a painting for example. Maybe that’s not a very good aspect, but as I’m very lazy, I like digital very much because you can do it with one hand.

Do you consider yourself an artist?

This is something I always had difficulties with, but the more I think about it the more I see myself as an artist. I see the reception of my images … people think I’m an artist. So, I started to think about it. I never wanted to become an artist. It is more easy to work on contract because when you work on contract you don’t have this responsibility of being an artist. Being an artist is very difficult – and is more and more fading away. As an artist, you always have to fight. Being a contract photographer is easier. You have a contract. You have a task. You fulfill the task. You have an aim and you do what has to be done. Maybe this was what I liked to do, but when I look back now, I see that I worked like an artist.

Why did you leave Spex?

Because things started to become repetitive and I was no more that interested. I was there in a parking house taking photographs of a band with concrete walls. They were so boring. They were standing there and I thought this is so boring. I knew it all. At the same time, I was in contact with a car-building company and I started working for them as a documentary photographer. I found it very interesting to see what is there outside the cultural area.

What has been the biggest challenge while taking photographs in Karachi? How can the exotic cliché and stereotype that’s being reproduced when the East is presented to the West be avoided?

I would see it the other way around. It’s so tense and so dense that it is a challenge to take photographs here. When the guys of We Are One (a Pakistani dance group, SJ) took me to Lyari, it was like I was in a punk rock concert. I love this kind of tension. Karachi is very fast. So you have to understand very fast. You have to act very fast. You have to look around. You have to look straight and when you look straight you also have to look both to the right and to the left. This is what you could call my work ethos – to be very aware. You have to be very aware to survive here and a place like Lyari is the center of being really strong to survive. This energy is inspiring, it stimulates me very much.

We Are One (Lyari, Karachi 2018) © Wolfgang Burat

But again, how can one avoid the exotic clichés? You told me that you consciously decided against taking certain kind of photographs. You stopped yourself: No, just don’t do it.

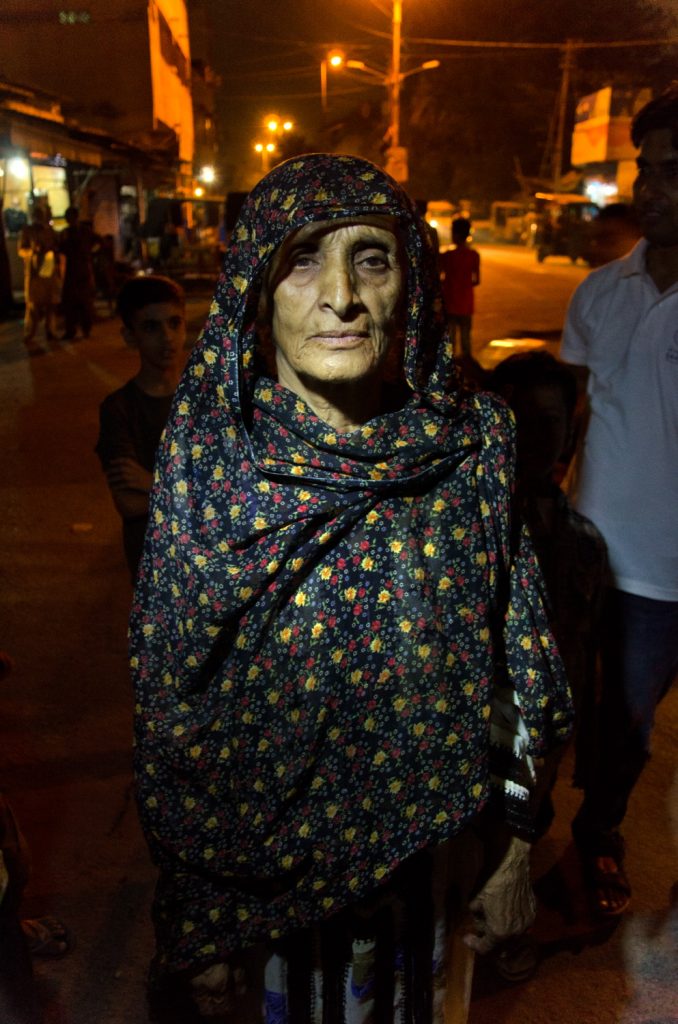

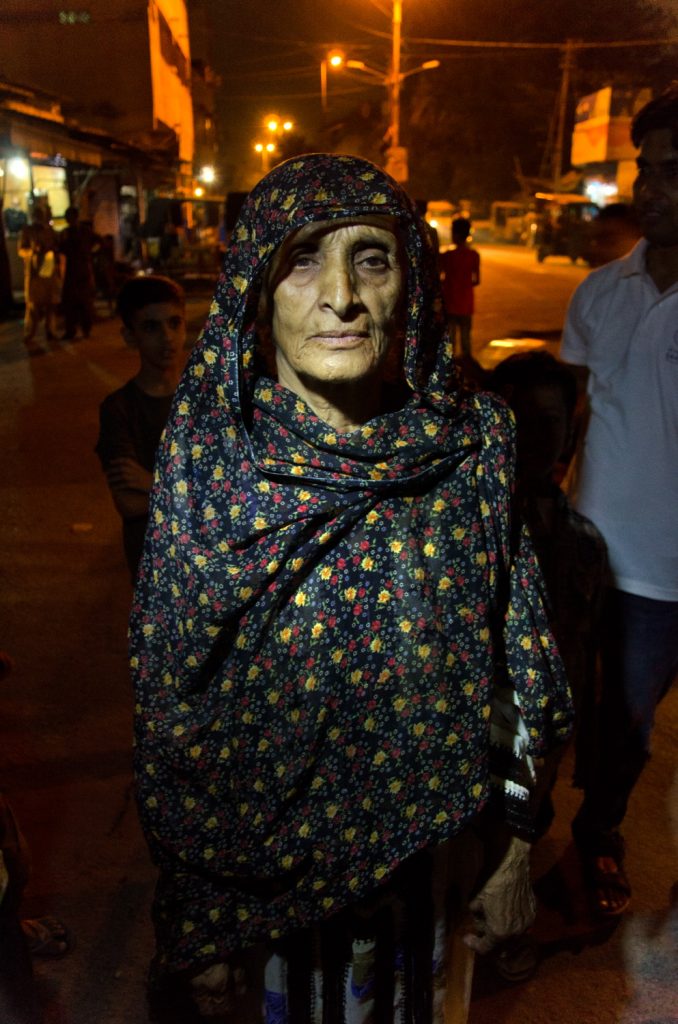

Yes, I thought about this a lot. When I see a man who’s lying in the dirt or a beggar with no legs, I don’t take my camera out because I don’t want this. I want to understand. I don’t want to reproduce some kind of surface of a western image of oriental existence. I want to show the things like they are. And that means I have to understand. It is a challenge to understand, because it’s hard to understand. So, I have to focus. I have to be open. I have to be quick. I had all of this with my old kind of photography – my preferred kind of work. So, the tension here is good for me, but I don’t think it’s good for the Pakistanis. I wish that they could get off this tension and could live a relaxed and happy life with an outlook to the future.

During the introduction, you stated that you want “to show special people… people in real conditions”. The man lying in the dirt or the beggar with no legs – that’s real, isn’t it?

Yes, but it also has become a cliché, an image of an image if you like. I don’t want to show the beggar as a cliché, but as an individual, as a special person. Everyone is special. This is the task that everybody who reflects others – be it in a portrait be it in a writing be it in whatever – has to do. They have to go deep into the other side and empathize. That’s very important.

Senescence (Lyari, Karachi 2018) © Wolfgang Burat

As I said, because it’s a cliché – and moreover, it is disrespectful. I’m not looking for that. This is social peeping and I hate social peeping. Social peeping is very common and people like it very much. You see drug dealers and heroin addicts in their blood and all this. This is disgusting and is a kind of peeping that I really hate. I don’t like that. I have heard that in Pakistan there are very popular crime magazines who love to show this. This is something I find really disgusting. It also destroys social interference.

Tell us about your worst photo session ever.

I guess that was my session with Can, a German band from Cologne, my hometown. They were very famous in the 70s. Many musicians in the 80s related to them or still do today. As far as I remember, I was called to take a photograph of them. So I arrived at their studio – and they told me that they didn’t want to stand together and I had to figure out a way to manage a photograph. They were all running around in the studio and talking. It was a reunion and those were the worst photographs I ever took.

Why?

Because I was not allowed to grab a situation. They didn’t want to work with me. They wanted to work with me, but at the same time they didn’t want to work with me, too. They wanted me there, but they didn’t want to work with me.

They didn’t want you to tell them how or where to pose?

They didn’t want to pose in any case … They just wanted some casual photographs while talking with each other.

But why? Those photographs could have been good.

Well, they were not. They were really bad.

Why?

No idea. Maybe I was too nervous or maybe I felt like I was not accepted.

What is it that you intend to capture in a photograph?

The situation I guess. I want to be there. But I only know if I was afterwards.

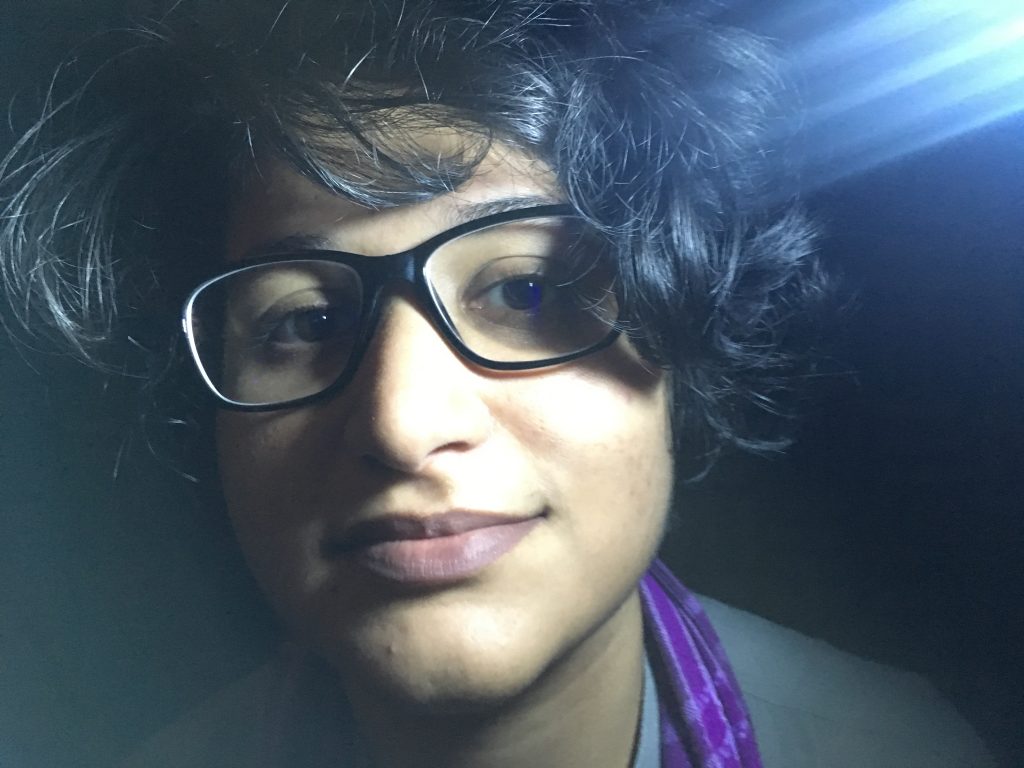

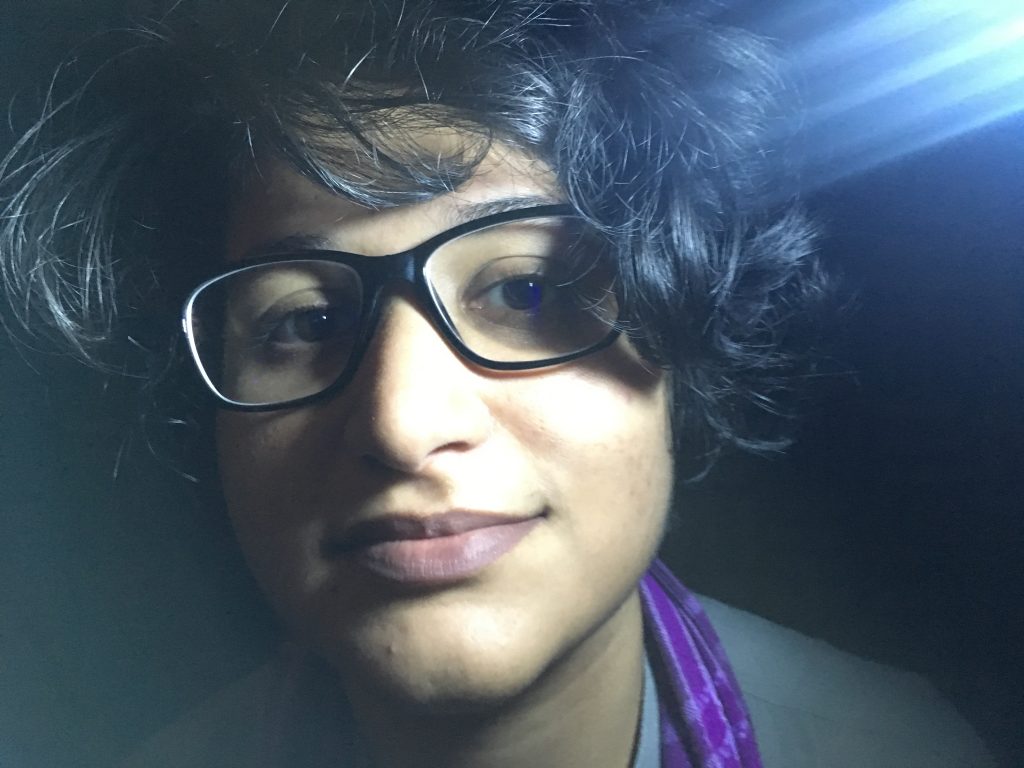

One of your specialties is what you call in German ‘der entfesselte Blitz’, to ‘unleash’ the flash. During your photography workshop at Habib University, you advised the students to unleash the flash – and in order to do that, take risks. To just go for it. But they didn’t.

Well, some of them actually did, but then they only presented the safe ones to us. They thought the risky ones weren’t good enough. So, this is about a certain idea of perfection that is in our heads – an idea that is being reproduced by the mass media. But it’s the imperfection if you like that is more interesting. A perfect photograph doesn’t challenge you – it doesn’t ask you to work with it. You look at it, admire it, but you don’t reflect. What I am looking for isn’t beauty if you like. I want to make an interesting picture. It may sound banal, but that’s it basically – creating something interesting. Not to compose something very carefully, to control the situation, but to let things compose themselves. I can’t explain it. I can’t give a recipe.

Media Studies Asia Editor-In-Chief, Saima Jawed, photographed with an ‘unleashed flash’ during the workshop at Habib University

Interview: Saima Jawed

Additional photos: Markus Heidingsfelder