“Operating on Happiness” – Interview with Alka Menon on Beauty Ideals in Cosmetic Surgery and the ‘Sociology of Covid-19’

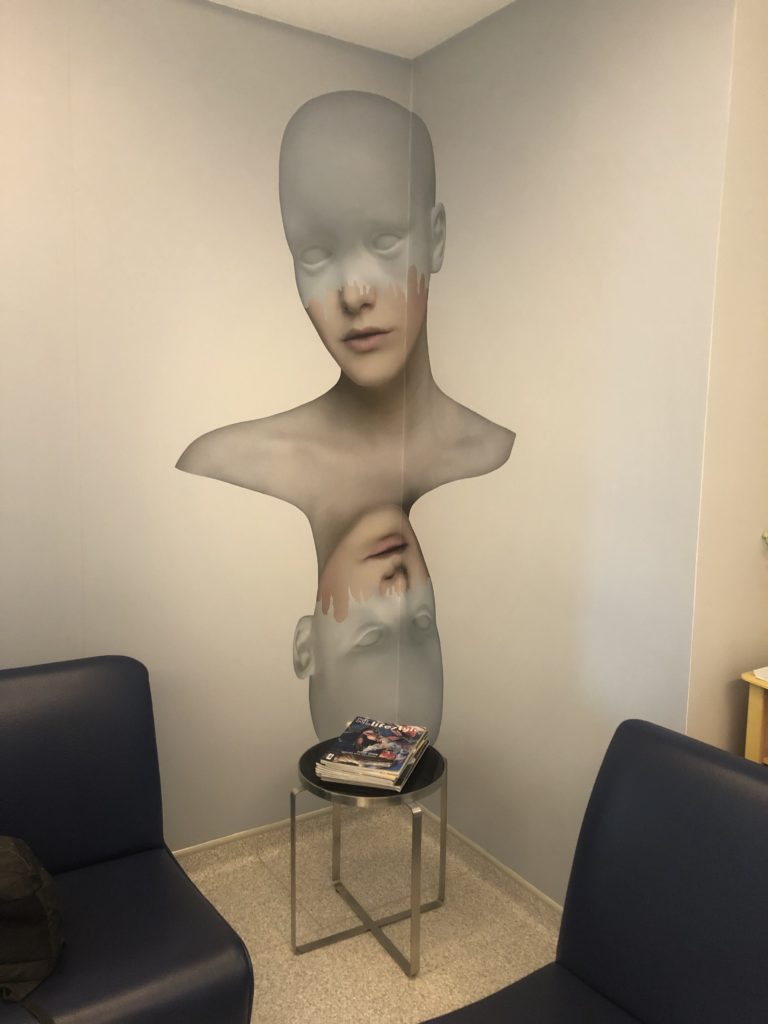

Waiting room at Dr. Kim Tan’s practice, Pantai Hospital Kuala Lumpur (Photo: M. Heidingsfelder)

Hi Alka!

Hi, Markus.

Let me introduce the two others first: This is Saima, our Editor-in-Chief, and this is Yap Khai Qing, a journalism student at Xiamen University Malaysia.

Hi Sama, hi Khai, nice to meet you guys.

I think Saima wants to go first, because …

Well, I have this strange obsession. I like to watch all these cosmetic surgery movies on the internet. That’s why I was happy when you agreed to do this interview. Can you understand this fascination? And did it maybe fuel your interest in the topic somehow?

So I should definitely begin my answer by saying I have never seen anything about plastic surgery, cosmetic surgery before beginning this research project. I found the phenomenon through a newspaper – the oldest form of media possible. But since beginning this, studying and learning more about cosmetic surgery, I can understand why these programs have taken off and what the appeal might be to people. Why it has become so popular. There is a voyeurism aspect of the possibility of transformation to it. And it’s also that cosmetic surgeons are often showmen, right? They have this sort of personality that is geared towards …

The camera?

That’s right. And so these TV shows … there was a lot of consternation about them early on from the professional society, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, and eventually the society came around and issued guidelines saying: Okay, there’s a responsible way to do this, and we don’t want to promote unrealistic expectations. But this publicity is probably better on the whole than just eschewing it all together. But now that there’s also Snapchat, some surgeons in real time film themselves operating on actual patients, with patient’s consent, and you know, it’s like … the appeal of all reality TV is it seems unmediated and organic and like you are peeking into someone else’s life. That’s what I mean by voyeurism. It’s not even – it’s not prurient, you’re not just interested for the sake of sex or something weird and specific. The appeal is to to understand what motivates the insecurities of another person and what the possibilities of transformation might look like. And so I understand that imagination on this is especially important and therefore interesting.

What comes to your mind when I (Markus) just say this one name: Michael Jackson.

Huge. Central to the discipline of plastic surgery. American surgeons blame slash credit him with setting back the field for people of color in the United States for decades, because he represented what most people don’t want and so people thought that plastic surgeons just did not know how to operate on anyone who was not white. But even internationally he’s a figure of total fascination, not just in the plastic surgery surgery community. I attended a presentation in Japan, and a Japanese doctor who had never met Michael Jackson – this was years after his death – gave an in-depth psychological portrait of where he was in his career, and what he was feeling during each of his four or five rhinoplasty procedures. The surgeon based this on media accounts, it was his own sort of reconstruction. This was just a fan, you know? So he used this as a way of saying, “Asian cosmetic surgery could have had a different approach and it would have been … and we could have saved his nose, you know , and that would have helped his self-esteem, and it would have been … he would have had a different trajectory, maybe he would be with us now.” It was that level of rewriting. So Michael Jackson is a cautionary tale for most plastic surgeons, because he was seen as crossing racial lines, going from black to white, but also general lines.

Some people say his beauty ideal was Liza Minnelli. And she just happened to be white. Very white of course in Cabaret, with all that powder…

Yes, I have heard that, too. I think that – you know that’s another one of those stories. Michael Jackson was a showman, and he had a sort of vision of what he wanted. He was really clearly tormented between a view of what he wanted for himself and what he wanted to display to the world. He had a very tortured relationship to fame and to his body. So he’s an example that everyone goes through this to some degree. There’s the human side that is yearning to burst free, that maybe could be unveiled by plastic surgery, and then there’s how other people will see this transformation and evaluate it.

Alka Menon conducts research at the intersection of race, medicine, and markets at Yale University. She received her B.A. in the Biological Sciences from Cornell University, where she was also a College Scholar, and her Ph.D. in Sociology from Northwestern University. Her research and teaching interests span sociology, science and technology studies, legal studies, racial and ethnic studies, gender studies, and qualitative methods. Currently, she is working on a book project on cosmetic surgery in transnational perspective, focusing on the multiethnic cases of the U.S. and Malaysia. Stemming from this research, she has also written on online reviews of physicians and the role of physicians as cultural gatekeepers and intermediaries. Her award-winning work has been published in Ethnic and Racial Studies and Social Science & Medicine, and has been supported by the National Science Foundation and the Social Science Research Council. At Yale University, she is also a Research Fellow at the MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies. (Photo: M. Heidingsfelder)

You told me (Markus) yesterday that Westerners very much care about what you call their ‘bodily integrity’. Can you elaborate a little on that?

Silicone is a good example. It is very commonly used in ‘nose jobs’ in Asia, which add a nose or augments a nose. But in the West – broadly speaking – surgeons are very reluctant to use it. They associate it with a higher rate of infection, they worry that it’ll slowly pop out … the evidence is mixed as to whether or not this is more dangerous than using material from another part of the body to build up the nose. This was actually a debate at plastic surgery conferences between cosmetic surgeons practicing in Asia and cosmetic surgeons practicing in the United States. Surgeons practicing in Asia argued that people in Asia would rather have ‘foreign material’, silicone, something synthetic put inside them than to take material from another healthy part of their body and use that.

Do you have empirical evidence for that? Some may say this generalization is – well, a little racist.

This comes from anecdotal surgeon impressions and observations of cosmetic surgeons discussing their techniques with one another at international meetings. To what extent does this play out in operating rooms? That’s harder to say, particularly in the absence of systematic statistics on cosmetic surgery. Patients are much less … there’s a sort of worry about injuring the one part of the body, to augment another in the case of cosmetic alteration. If you’re trying to fix something that has broken, due to accident or illness, it might also be seen a little differently.

So the line to define bodily integrity varies from culture to culture, from East to West?

I guess the counter example that came up at the same conference when the surgeons were debating, was people put silicone in their breasts in the U.S. all the time and they do not see it as a violation of bodily integrity. Right, so it’s like an arbitrary distinction. People have ideas about face and what a face means, and be unwilling to consider silicone implants there. But their reluctance to use silicone may not extend to every other body part so it’s part of the contradictions that are rampant in the field.

What do you think, what motivates people to undergo multiple plastic surgery procedures?

I don’t know. My research is focused a little bit more on surgeons’ motivations for granting procedures to patients, and their interactions with each other. So I have mostly their perspective, a little bit of perspective on patients, about their relationship with their surgeon – but their motivations for why they are undertaking procedures, how it changes their own biography, I have a pretty limited perspective on that based on the data that I collected for this project.

And anything you get from them is just what they tell you.

Exactly, it’s their accounts. Which I think is interesting to know, but the narratives are stories that people tell about why they take the actions that they do, their explanations for external audiences. People are full of contradictions for themselves.

How would you differentiate between cosmetic and plastic surgery?

The overarching term for the field is plastic surgery. It can loosely be divided into cosmetic surgery and reconstructive surgery. Cosmetic surgery – sometimes known as aesthetic surgery – is about improving the overall appearance, enhancing it. Reconstructive surgery is usually done with the aim of improving or restoring function after injury, accidents, illness or congenital abnormalities. Now this sounds like a very hard and fast distinction: cosmetic on the one side, reconstructive on the other. And I think you can identify procedures that would be identified that way on the poles of the continuum. Cleft palate surgeries are typically seen as a reconstructive surgery done on babies or children that helps children to be able to eat, to talk at the age appropriate time and prevents other potential complications. That is usually considered an example of reconstructive all over the world. An example of cosmetic surgery would be breast augmentation in a young, healthy patient. The cleft lip, if you can’t swallow or you have difficulty chewing because of the way your mouth is shaped, that seems pretty reconstructive. But there’s a lot in between, and of course, reconstructive procedures have cosmetic considerations, to look normal or to look the way that you did before. There are procedures that’s neither fully one nor the other, surgeons will say … you can think of them as a little bit reconstructive or necessary, or that they should be covered by insurance, that’s the other major divide.

Waiting room at Dr. Kim Tan’s practice, Pantai Hospital Kuala Lumpur (Photo: M. Heidingsfelder)

Reconstructive is usually covered by health insurance or paid for by the state, whereas cosmetic surgeries are out of the pocket by patients on their own. An example of that is a nose job. If you walk into a door, then maybe you need something to be fixed. But then, the aesthetic may be as important as the inner plumbing for your breathing, and so you’ll get some insurance coverage for that. But in different countries, different procedures are covered by insurance. So for example in the United States, breast reduction procedures are seen as reconstructive, because it’s associated with alleviating back pain, and shoulder strain. Whereas in Malaysia that’s seen as cosmetic, and in Brazil its sometimes seen as cosmetic because a smaller figure, a smaller breast are seen as more aesthetically pleasing, so you may not be covered by insurance.

But often when surgeons are talking about the ‘in-between-ones’, it’s with the aim of saying that there’s legitimate motivations for people undergoing cosmetic surgery that are akin to the motivations for people undergoing reconstructive surgery. It’s more of a narrative that accounts of how these things are related, because they’re trained to do both. Every plastic surgeon who goes through board certified training in any country learns primarily on reconstructive patients. And then, as they become more senior, they move into a private practice, perhaps from government practice or public service, and then they might see more cosmetic patients. So they see the similarities, the continuities, in why people are looking to change themselves.

Is it true what Markus told us, your scientific career started off with rats?

Yes.

So now you moved on to humans. Not a big difference between the two …

Rats are smarter!

I (Saima) agree.

But humans are more social.

So how did you end up doing research on cosmetic surgery?

I was doing neurophysiology, giving electric stimulus in the rat’s brains, and then measuring their responses. Seeing what part of the brain was activated having recorded their response that way. So I majored in neurobiology. When I studied neurobiology, I discovered this field of Science and Technology Studies, which talks about the social aspects of how knowledge is made, and in my case, how I could take that weird electrical signal coming from this rat brain and make an inference about Alzheimer’s disease in humans. That’s a pretty big leap for someone sitting in a room with a half dead rat waiting there and seeing some spikes on a screen, you know? There’s a lot of work that goes into making that coherent, and STS is a field that explores that work and the dynamics of how the laboratory structure can affect the kind of knowledge production.

You started to reflect on what you were doing there …

Absolutely. Absolutely, because it felt – you know, I could not derive any generalizable knowledge sitting there myself as an undergraduate in front of that rat. But the PI, postdoc and graduate students did. And I was killing them. So I felt motivated to understand what could be underlying this. The field of STS helped me think about knowledge production and medicine and how do you make inferences about human health, and what kinds of people are alike and what kinds of people are not alike … How do you make enough standardizations to be able to say that this drug or this therapy is going to make a difference in people? So I worked in public health afterwards. I became especially interested in health disparities by race, which is a huge issue in the United States, but is very structurally and socially shaped and in terms of distributions of resources … But a lot of the research looks at things like genetics to look for explanations for why there are these differences.

Really? They are still doing that? That’s racism right there!

Again, this became a knowledge production thing. How do you tell, you know … it seems so obvious there are differences by race in medicine in the United States, but who’s a member of what race for purposes of science? As a city public health worker, I put people in those boxes, and when you produce knowledge about somebody in one box, does it apply to people of another box? Why or why not? So I was looking for cases into medicine of specialties or diseases that I could explore, these questions. And at the time there was a lot of concern about genetics and the potential for genetics to do this, but then I read in the newspaper an article about plastic surgeons and it quoted a plastic surgeon saying: ‘The moment someone walks into a room, I know what ethnicity they are, I can tell you what they want’. So here was a doctor making a claim of expertise based on race that was entirely about appearance. He didn’t care anything about genes but he’s making a strong claim that he has expertise in something about those racial or ethnic group that is obvious from the face or the body of the patient. So I started looking into this person. And then I found that there was a literature that develops standards of appearance within plastic surgery, ethnic-specific standards of appearance differentiating them along different racial or ethnic lines. From there this sort of went outward, trying to understand how such a thing could exist, and whether or not people paid attention to it outside of this very narrow specialized field of academic medicine. That became the project.

You talked to a lot of surgeons. It seems they actually liked to talk to you?

Yes.

Why? One would assume that this is something going on behind closed doors …

They have this sort of personality that is geared towards microphones!

Yes, and they like the interaction with people. That’s why they do cosmetic surgery! As opposed to general surgery where you are in too much pain with your appendix that is busting to really have a biographical conversation, right? Some surgeons even called it ‘psychiatry with a scalpel’.

That’s nice.

You want to understand the person, what motivates them to do what they’re doing, you know? You want to get a sense of the person, so they like to do that, they like to talk, and like to interact. That’s one of their skills.

Have you observed – ‘produced’ – any differences between Asian and Western surgeons here?

They’re all good at talking to people, relative to their peers in daily life. It would be difficult to say that, because these are just cultural differences. Malaysians are very chatty …

I (Khai) agree with that!

American surgeons were chatty with me, too, but less chatty with patients. There’s this awareness … more of a professional boundary, that they were toeing the line on and sometimes crossing because it. For some, that was part of their identity as a macho, ‘devil may care guy’, that they recognized that there were these lines and only sort of maintain them …

Did you talk to any women/female surgeons?

I talked to about four or five women in the Malaysian context, and then in the larger project, it was about 15 or 20 total. Women surgeons do have a different interactive style than male plastic surgeons.

Especially when they talk to Alka Menon!

Right, but I guess what I was surprised by is that they were both very open. I’ve been warned that to expect more formality in both the U.S. and in Malaysia, but I think that they wanted to give an account of what they were doing to someone. This can be a pretty lonely job, usually you’re not working with any other plastic surgeons in a practice, they’re sort of competitors, so being able to share this with a non-competitor to explain themselves, it felt like a form of service to them. I taught medical students, I told them these cases were going to be medical ethics cases in a classroom, so participating in interviews that would inform classroom discussions a more direct form of giving back. So they came up with things that were difficult, they didn’t just, you know, flippantly give me their description of their Porsche or anything like that. It was actually pretty thoughtful. They deserve … they’re more multidimensional than some of the TV shows and things like that would suggest.

But they maybe also just want to be recognized. So they try hard to appear more philosophical than they actually are maybe.

I think that’s absolutely part of the case. It was the interaction that brought this out. Some of them have been active writing about these sorts of things for an audience of their peers. For some of them, there was more of a track record of engaging on these questions openly. But it varied.

The one thing that you found out and that’s just beautiful, it is a kind of punchline – that most of them told you: ‘Beauty comes from within’.

Right, but then, what are they doing? What are they standardizing? What is this ideal of beauty to which they’re aspiring, what do they call that? It dodged a real question, because they still have differences in what they think is aesthetically desirable for patients and what their specialties are and their techniques to achieve them. So you know, you can … I think they want to avoid the term, because it has a morality connotation that’s unavoidable. And physical appearance does not, you know. They also know that people themselves often think of beauty this way, that there’s this fearlessness associated with superficiality of skin deep beauty, and that the real underlying beauty is something that is intangible and personality based. That comports with public understandings in many countries. This is what they believe, what they were taught to believe, but they didn’t square that contradiction with the daily livelihood and how others would perceive what they’re doing is operating on beauty.

Some of them spelled it out, some of them said beauty is the person at the office that can get along with anybody. Or beauty is like an easygoing happy person. So what a lot of surgeons told me is that they operate on happiness. Which is actually a really useful framework for thinking about cosmetic surgery, because that can explain why the outcome is maybe not aesthetically normal or aesthetically in line with any sort of philosophical or other tradition.

A selfie with Hadi from Indonesia, master student of the Institute for Ethnic Studies (KITA) at UKM, 4th March 2020

I also think that questions about gender and power and media are really interesting and huge in this subject area. Cosmetic surgery is a nice case to begin to untangle the way that these things are networked, because they’re not employed by Hollywood. Plastic surgeons might have a little clinic by themselves, but they absolutely benefit from movies that promote a sort of thin ideal of beauty. Even as they’re not directly engaged in conversations that would make that appear on screen. More and more people are overweight obese, a demand for a more slender figure is something they’re helping create right off the bat, sort of something surgeons can offer people. That’s just one example, and the fact that surgeons in both the U.S. and Malaysia have traditionally been male and that most patients are women, there’s a certain inherent power dynamics there. Surgeons are going for normative things, they’re not interested in experimenting with the human body, they don’t want to give anybody a third nose or you know, a third beauty mark or things like that. Usually you wouldn’t have more than one or two, maybe they would envision a third dimple, but that’s not hugely radical. While there’s potential in thinking about the body as an opportunity for self expression …

As a medium.

… as a medium, the issue is: You’re dependent on surgeons who are gatekeepers to what they think you should look like and what they want to be associated with.

We lost the gate gatekeepers in the media, but in cosmetic surgery, we cannot afford that. Yet.

There are some amateurs, that’s the danger, there are people who will inject silicone to create buttocks lifts or butt augmentations or butts implants, the appearance of these things. Sometimes they’re affiliated with a medical field in some way, but they’re not surgeons. Sometimes the silicone they get is not medical grade and there are complications. Historically, people did this with wax. Beauticians would inject wax into the face to change the nose or profile of the cheeks, too. And that can be very dangerous. So I mean there’s something to if you want to modify yourself and use medicine to do so, go for the sterile field, clinical surgical suite but that makes cosmetic surgeons the gatekeepers, and they might be some of the most conservative with how to change the body … that’s the trade-off, you know. You’re not going to be able to do anything beyond what anybody has imagined if you were with them. So this question of having the cosmetic surgery market regulate itself is really interesting, because there is some amount of professional regulation with professional societies in each country, and medical examiner board. If a patient dies, there’s an investigation, that’s again the logic of why you would go to a plastic surgeon as opposed to a nurse for this kind of thing. They are licensed, and there’s some accountability and investigation if it goes that way. Surgeons have medical malpractice insurance. But the market itself is so variable and dependent on patient satisfaction that online reviews also become a major way of more informal regulation. People get to know surgeons to evaluate their styles, surgeons get feedback from patients on what they thought went well or didn’t go well, so there is some awareness of their perception probably, and that is unexpectedly a method of at least some regulation or accountability outside of a government framework.

I (Markus) showed you these Cindy Sherman photographs lately. One can say that she did a kind of parallel research on cosmetic surgery, only using a different medium. Any thoughts on this?

Well, I think that people who have done arts or performing arts with plastic surgery open a really interesting conversation about both the media and the body as a possible medium for art. But they also experiment with the public in a very interesting way, because a lot of people, when they do plastic surgery, they don’t make it public. People who have undergone surgery want to look natural afterwards, and they may tell their friends or family ‘This has happened’, but it’s not something that you would want to know about someone you meet for the first time at a coffee shop. Whereas these artists who make art based on undergoing procedures, they’re making that conversation public . That’s a critical dimension, but that’s what plastic surgery is about, it’s about the public’s perception. It cannot be disentangled. So if you live in society, the public will be seeing you after this, even if you are doing it for yourself – that’s a factor. So art really opens up that conversation in a good way, especially photographic art.

Personally I think people are nervous about changing their body, about modifying the body. There’s this notion of bodily integrity we talked about. You have limits, and they are biological in some way, but they’re also just what you experience. Cosmetic surgery suggests that those limits are not so limited. Not that it enables just anything either, right? Cosmetic surgery cannot turn you into a shark. It cannot help you breathe underwater. There’s a narrow range of possibilities ultimately, but also it enables modification at all, which is not how we think about bodies.

Would you say that cosmetic surgery is a promising sector for Malaysia’s economy?

Malaysia has invested to some degree in medical tourism more, probably, starting with procedures like heart surgery which you know can be scheduled a little bit in advance. After the Asian financial crisis, Malaysia pivoted to making available hospital space in private hospitals, especially for patients from abroad, especially the Middle East, to undergo procedures here that can be scheduled in advance. The hospitals meet international accreditation standards and generally have good reputation so they’re open for that, and cosmetic surgery can sort of slot into that as well patients from New Zealand and Australia, where procedures are very expensive, might sign up for packages with companies to come and do procedures here. So this kind of medical tourism and facilitation of these middlemen companies to help patients manage the whole experience has been a little bit of a growth area in Malaysia. It’s hard to say whether that’s a direction that will be, you know … what sort of pressures it will be subject to economically.

So medical services are a continual growth area in terms of there’s never … you can always think of new procedures people might need or want, especially in a cosmetic space. In that sense, the trends might change. But the underlying investment will be good. For something like the corona virus, when everybody cancels travel and doesn’t want to do anything outside of the borders, this is a case then where such an investment … it’s like any tourism, it’s subject to downturns in that way. And it’s a luxury good, it doesn’t have to be done.

So the answer is yes?

It’s the answer the Malaysian government has taken, they’ve invested to some degree, but cosmetic surgery is not where they put the majority of their effort. Medical tourism is. Because I think there is some wariness of this particular thing, cosmetic surgery. But if you invest in medical tourism more broadly, cosmetic surgery can be part of that. And they certainly have not discouraged it.

How do you relate the role of religion and religious acceptance to cosmetic surgery?

Thank you, Khai, I think that is an interesting question. It’s certainly dynamic and changing …

That student you talked to today, Hadi, he said this is the body given to us by Allah, so …

That’s right, and one should be grateful for it. There’s this attitude of gratitude, towards what you have, and a non-intervention attitude towards anything that’s common in many religious treatments of cosmetic surgery, to think of the body as a sacred space that should not be intervened upon.

Not to forget that vanity is considered a sin in Christian religion.

Yes, absolutely. Surgeons usually did not say much about the role of their own religion in motivating them, but the ones who did were Christian, and the Christians said: I’m uncomfortable with procedures that too clearly aim at enhancing one’s sexual appeal or sexual attractiveness. That was the specific way that it came up. I think even as there are religious reasons for plastic surgery in terms of the attitudes that they prescribed towards the body, there’s differences of interpretations and opinions on what is permissible and what’s not. And so you think about the line between makeup and less invasive procedures like Botox or fillers and then more invasive procedures like surgical procedures, such as abdominoplasties, breast augmentations. And it might come down to what the problem is, what else is going on. Or if you have an asymmetry, maybe that’s okay to change, but maybe a breast augmentation putting silicone into the body, that’s seen as something … So different religions … There’s a plurality on where they would draw the lines of what is acceptable and why. In general, I would say none of them wholly embrace the idea that you should take the body and do anything you want with it.

What about race and ethnicity? You said your whole research was more or less motivated by this statement, a surgeon saying he knows what race someone is the moment she walks in …

I think what’s interesting in my research about race and ethnicity in the cosmetic surgery market is that race works in a different way at the global level than it does in an interaction between a surgeon and a patient. Surgeons in Malaysia might say that they’re experts in Asian cosmetic surgery, and in doing that, they appeal to people from different Asian countries, but especially from China or those of Chinese descent. But they can communicate with surgeons in the United States, who operate on patients who may be of Korean heritage and Japanese heritage, by saying that this is what they learn on treating Asian patients … So the racial categories expand at the global level, because it depends on the other that you’re comparing to, and then they contract when you’re in an interaction between a doctor and a patient.

You might in fact … you can imagine that … Ethnicity and race do not have to be discussed verbally at all in an interaction between a surgeon and a patient. As a patient, you show the surgeon a picture you have, you know? And then you have a discussion based on modifying the picture to see what should be done. Race and ethnicity don’t necessarily provide any additional information or communication value. So there’s something about how the transnational nature of the field makes race and ethnicity salient in a different way for ideals to circulate across the globe. But in a specific country, the common sense version of race comes into effect and you’re not necessarily … it expands and contracts to what the space is.

I thought that there is this kind of ‘white’ ideal, that Hollywood ideal everyone goes for …

A lot of research that focuses on especially young women and perceptions of beauty in specific places and times finds that people recognize this universal or Hollywood ideal. But many people don’t think of it as something that they want. They just know this is what the world thinks is beautiful. But if there’s a local beauty pageant you’re not going to pick the visiting exchange student who looks like that to win the pageant, right?

What about your looks? It sometimes seems that especially people in the West make research qualifications on other regions of the world dependent on appearance – if you’re ‘from there’, you automatically qualify.

People in the US don’t know exactly how to identify race always. Race seems like a self-evident thing, but people aren’t so good at telling, right? Almost nobody in the US knows that there are Indian people in Malaysia. Whereas in Malaysia, everybody knows I’m Malaysian Indian based on my name and how I look. But in in the US when surgeons would actually guess what my racial or ethnic heritage was, maybe one in four got it right. It’s not so obvious.

When we (Markus and Alka) drove back from UKM to this interview today, you pointed at these billboards, and you said the reason why we see so many white people on these billboards is not because people here have a preference for the Hollywood ideal, but for a very simple reason …

This is just an anecdote from someone who works as a graphic designer, making advertisements for an aesthetics clinic. She was saying it’s very hard to find stock images for free or for very cheap of non-white people of Asian different kinds, of Asian people. So when you see these, when you’re bombarded with pictures of white people in Asia, you see this in India too all the time – all underwear ads are white people -, there’s multiple reasons why this could be. But one could simply be that there’s not as many stock images available of other people. So it’s just that this is what’s free, you know? It’s not that this is aesthetically better, it’s available. So it’s also an infrastructural problem. If these things were developed and then made online for free … there’s actually demand in to depict people who look more like the people on the ground.

Alright, I hope the Asian agencies are listening: There’s demand out there, go and make photos of smiling non-whites available!

You are also an expert in the sociology of infectious diseases. What are your observations related to the Corona virus outbreak? Any new insights – or just confirmations of what you already knew?

I think there are surprising developments in this outbreak. In the modern era, we have not seen quarantine and isolation measures of the magnitude undertaken by countries such as China, South Korea, and Italy. Quarantines can slow the spread of illness somewhat, but have not generally been thought to be effective for a health crisis of this magnitude, let alone feasible to undertake. We will see as this outbreak progresses whether and how they work at new scales.

Another observation is the variability between country and regions in their testing policies. Some places, like Singapore and northern Italy, aggressively tested people and found a higher caseload as a result. Other places, notably the U.S. and Japan, decided not to conduct widespread, early testing, having more strict criteria about who was eligible for the Covid-19 test. This also reflects limited capacity for testing in some places, including the U.S. This is tantamount to different approaches to disease detection and prevention. Singapore and, increasingly, Italy are betting that exhaustive surveillance and comprehensive tracking can somewhat mitigate the spread of the illness. And they seem to hope that sharing this information with the public will build trust and confidence in the government’s management of the crisis. But many countries, including most “developing” countries, lack the resources to mount such a response, but it is particularly interesting that the U.S. did not ramp one up. Going forward, the varying caseloads across U.S. states that have had different testing policies, as well as European nations, could yield some useful insights for future disease prevention efforts.

I (Saima) find the social consequences much more drastic than the health effects. And I don’t think it is enough to have the governments share information … I think they should also share the decision-making. Not having a political rally or a soccer game – fair enough. But closing all the schools? I don’t think that is ‘healthy’ for an open society.

I (Markus) agree. We need to decide what we – as a society, as ‘the people’ – are okay with. And what is not acceptable. These lockdowns of whole areas, that is just crazy. Isolating old people.

But all they want to do is to disrupt chains of infection. So my (Khai) question is how we can make sure to keep up a functioning and democratic society while at the same time stopping this thing from spreading.

How has Covid-19 personally affected you? Apart from the fact that you were not allowed to enter Xiamen University .

It has directly affected my travel plans. I had planned to stay in the Southeast Asian region for at least a couple of months. As airlines reduced flights back and Covid-19 spread in Malaysia, where I am visiting, as well as in the U.S., I decided that I should cut short my trip. Public events and life are increasingly circumscribed in both countries. But I’m going back early to assuage worried family members, and to reduce the chances that I end up having to take a longer, more complicated route home as flights continue to be canceled. I’m not sure that the U.S. is much better positioned to handle Covid-19 than anywhere else, but crises are times when one thinks about citizenship and state support. The U.S. healthcare system may not be especially well suited for this sort of crisis, but it is one I know how to navigate, and the U.S. is where I have the most community support should I need to draw on it. So I’ll likely be staying closer to home until panic subsides somewhat, and a clearer picture of the social and biological risks of Covid-19 emerges.

What’s happening next? Where’s your research heading to?

There are many possible directions. I’m certainly going to continue to keep an eye on the Malaysian beauty scene. The thing that I’m often drawn to are the marginal cases in medicine cosmetic surgery. But obviously there’s huge overlap with popular culture. Another example of something like that is breastfeeding of babies. It’s medical, there’s a lot of medical attention to the benefits of exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months, but there’s plenty of non-medical aspects, the sort of amounts of maternal leave that mothers, new mothers get if their working impacts their ability to do this. How you regulate milk – human breast milk, as a product or as a human tissue, can influence where it can go and who can use it. These kinds of things. So I’m always looking for that kind of case that’s on the margins that can shed light on the larger phenomenon.

Ok. Travel safe, happy landings – and thanks a lot for this interview.

Ramze Edut, who invited Alka to give a talk at IKMAS (Institute for Malaysian and International Studies) and Alka Menon in front of the IKMAS building, 4th March 2020, KL (Photo: M. Heidingsfelder)

Interview: Saima Jawed, Yap Khai Qing, Markus Heidingsfelder. Transcript: Saima Jawed.