“Reaching Out Across the Border: Spoken Stage in India” – Interview with Zoha Jabbar by Saadia Pathan

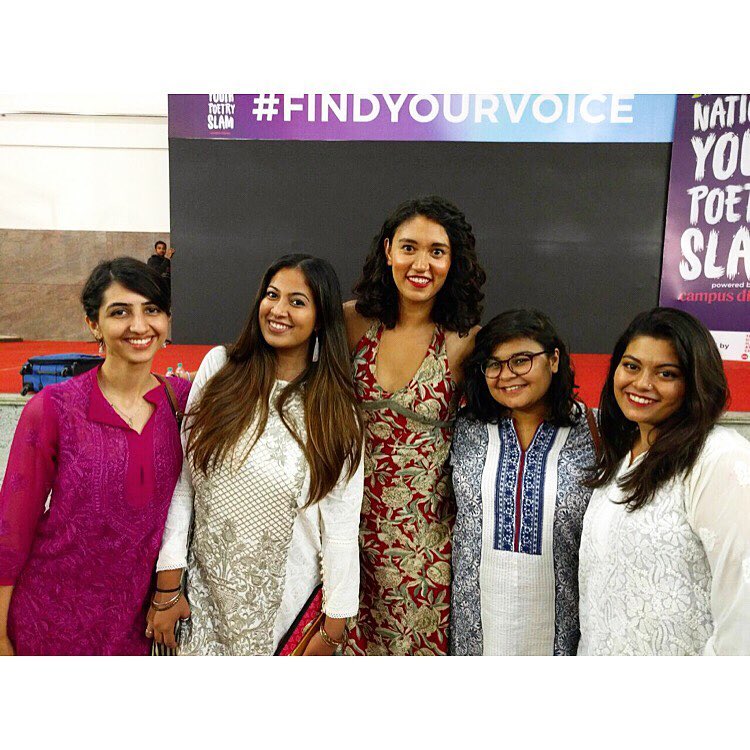

Spoken Stage is an organization that promotes the art of performance storytelling and spoken word poetry in Pakistan. It was created by Mariam Paracha in 2013, because she felt that there was no platform for youth in Karachi to express themselves, so she created a literal platform. It was a portable booth that she would carry around with her to visit schools, where she would recruit poets. ZohaJabbar was one of these school poets, and has been working with Mariam since the organization began. Starting from a regular performer, she is now the managing director of the organization. In September, Airplane Poetry Movement hosted India’s first ever National Poetry Slam, and invited Spoken Stage along with teams of poets from colleges all across India. I had Zoha sit down with me and share her experience.

First of all, congratulations. It’s great how Spoken Stage has been growing over the years. It’s taken on a new form.

Thank you. Yes, we have more of a social media presence and followers, and now we organize poetry showcases and slams all over Karachi.

And Airplane Poetry Movement, that is kind of like your sister organization across the border, right?

Yeah, it was founded by Nandini Varma and Shantanu Anand around the same time that we started up.

I wonder why they call themselves Airplane Poetry Movement. As if they’re a school of poets who write about airplanes …

I wondered about that too – I actually asked Nandini why they named their organization that, and she said it was sort of a tribute to hers and Shantanu’s favorite poem, For Those Who Can Still Ride in an Airplane for the First Time, by Anis Mojgani. It’s really a beautiful poem, and I can understand why they would be so inspired by it.

And Campus Diaries was also involved – who are they?

Campus Diaries is the parent organization. It was started by two college roommates when they found that there was no real support for college students across India. They started this organization as a way to provide resources, help, and support to students who needed it. They organize many youth events across the country, and Airplane Poetry Movement is a chapter of Campus Diaries. They’re the ones who actually funded us, and we met some incredible people there. We went to their office quite often, and it was a lovely little house in Bangalore, with a gorgeous terrace where they would shoot most of those videos. It makes me sad to think about that actually, it was just this place that was bursting with creative energy and we shared so many moments on that rooftop terrace where we spoke to our neighbors about poetry and politics.

So when they invited Mariam to Bangalore, they also asked for Zoha Jabbar …

Mariam was asked to be a part of their jury for the competition, and they didn’t ask for me specifically – they asked for a team of poets from Spoken Stage. So Mariam asked me to go, and to select some other poets to take with us.

And you decided to bring Shameneh. I think she’s brilliant.

She’s an incredible poet, yeah. There were four other poets who accompanied us, and they were all chosen because they’re just great at what they do.

This was your first time travelling abroad – and the first time you rode an airplane, right?

I didn’t really ride it, Saadia.

One day you will! Anyway, how did that feel? We’ve accepted flying ten thousand feet above the ocean, while watching the latest blockbuster movie, eating and drinking as normal …

You know – it was surreal. I mean obviously, I knew we would be flying, but actually watching the city shrink beneath you and then you’re flying above the clouds. It’s truly magical – it made me feel small, honestly. Entire cities can fit into the span of that small airplane window, and it made me feel like I was always worrying about the wrong things – and that none of the stupid petty shit actually matters. During the journey, I took six flights and every time the plane took off, I would feel the same sense of excitement and magic – I don’t know how people are so used to that feeling. I honestly never want to lose that perspective. I was traveling with five other people, and they knew it was my first time so they went out of their way to offer me the window seat and held my hand during take-off, it was wonderful.

How did you feel about going to India? A Pakistani going to India, that’s always a big thing, right?

I’ve always wanted to go to India, because I feel like so much of our history and our culture was lost to us when these borders were created. There is hatred and animosity to this day, but it was all constructed by outside forces. I was looking forward to traveling to the part of the land that we lost, and I felt a strange connection it. I had also never traveled before, so of course I was very excited.

I know you crossed at the Wagah Border. What was that like? Do you feel like this border is just – I don’t know, symbolic?

The thing is, yes, in a lot of ways the border is symbolic, but at the same time, it’s a very real border where there are rangers patrolling it on both sides. There’s a line zero, where you must go through a long bureaucratic process and answer like a hundred questions and go through body scans and baggage checks – so it’s also very real. The division is very clear. It was difficult crossing that border – we had to first fly from Karachi to Lahore, then drive from Lahore to the Wagah border, get to the Pakistani departures area where they regarded us with suspicion and mistrust and then we had to walk in the heat to get to the Indian gate and then to Indian arrivals. They were much nicer there though – in fact, we were amazed by the hospitality of everyone who found out we were Pakistani.

So you felt that separation – and at the same time, you didn’t.

Yeah, because it’s really not that black and white. In many ways, I felt it – the minute you cross that gate and enter Amritsar, you see men with turbans instead of skullcaps, the air is cleaner and the colors are brighter. I actually had a strange moment where we were waiting at the Amritsar airport and I asked around for a lighter. Immediately, there was a reaction and people would hurriedly say, “I don’t smoke” and walk off. An airport guard discreetly slipped me a lighter and told me I should go outside to smoke. When I was smoking outside, there were some families who stared at me openly and looked away when I looked back. I was later told that smoking is strictly forbidden in the Sikh religion, and that smoking openly in Amritsar is the equivalent of drinking publicly on a street in Karachi. But at the same time, no – I didn’t feel a separation and there were moments when I forgot we were even in India. It felt so familiar – we looked the same, we spoke the same way, and we shared the same history.

Tensions between the two countries increased shortly after you came back. While you were there, how did you feel the relations were?

If you saw the way the Indians treated us, knowing we were Pakistani, you would forget that there were any tensions at all. They were so welcoming and so hospitable. And after the event, many of the poets we met added us on Facebook, and I see the stuff they share and post, it’s all very anti-war. But then again, we only met poets and activists, so we can’t say everyone thinks like that. Just like in Pakistan, you have people who just want peace and good relations, and then you have the nationalist fundamentalists.

Tell us about some of the people you met.

We met so many incredible people first at the Campus Diaries office. There was Nandini and Shantanu, who are two of the sweetest people in the world, and then there was Sumit, the founder of CD who had arranged everything – he cracked the worst jokes with just the most deadpan expression and we would laugh so hard every time we were around him. There were people who went out of their way to make sure we were safe and had what we needed – Nikhil, Rishabh, Swadesh – they just took us everywhere we wanted, and took care of us and made sure we were comfortable. I mean for they wouldn’t even let us pay for food or cabs, they were almost unbelievably nice. Then of course, there were all the poets we met – brown poets who made us cry with their words about partition and history, and those who spoke about LGBT issues, and a sense of isolation – we met these people and realized that we are all so similar, no matter where we live and what side of the border we fall on.

You also met one of your idols, Sarah Kay. First of all, what do you like about her poetry?

Sarah Kay was like the gateway drug to spoken word poetry for me. Her poem B was one of the first ones I ever heard and it’s really how likeable she is – her grasp on words and her performance that draws you in. She’s really sweet and she creates these lovely images and metaphors, and she uses so many puns. One of her poems is called Love Letter from a Toothbrush to a Bicycle Tire, and in it she says, “They said that you would tread all over me, that they could see right through you, that you were full of hot air, that I would always be chasing, always watching you disappear after sleeker models, that it would be a vicious cycle.”

That’s great. I guess I’m in love with a bicycle, too. Is there also a Love Letter from a Bicycle to a Toothbrush?

No, but I hope she writes one.

Me, too. What else do you like about her?

I feel like Sarah Kay is a real feel-good poet and listening to her leaves you with this happy fuzzy feeling. I got to watch her perform live though, and that was magical. She just becomes such a tigress on stage – she never fumbles once, never forgets a line, and she’s just so energetic and powerful. We got the chance to meet her later, and she was just so sweet – and very tall. She told us she loved our pieces and even tweeted about us – I mean, that was wild you know? To have someone you look up to so much say something like that?

Do you know what she thinks of the Subcontinent? Is she familiar with our poetry, our poets?

She has been to India a few times before, and she has a couple of poems about India and Indian culture.

How did you get around India?

Bangalore is actually very different from Karachi in that aspect. Most people in Bangalore aren’t actually locals – they are students and young professionals from all over India, so it’s kind of like the New York of India. These people usually don’t have cars – we didn’t meet a single person who had their own car. They either ride bikes and vespas, walk, or use Uber. It was amazing to see all these women in their brightly colored clothes moving around the city on Vespas. I even rode on a bike once with Rishabh and it felt incredible. The best part was the walking though. I really love walking, and I don’t get to do it much in Karachi. In Bangalore though, the weather is so lovely all the time that you want to get outdoors. We would walk down streets at 2 a.m. and it wasn’t a problem- we could wear what we wanted and do what we wanted, and as women, that’s very rare. Karachi isn’t really a pedestrian friendly city – most people are expected to have cars and bikes are nuisance. You don’t even see that many women driving cars, let alone riding motorcycles. Walking on a street in a Karachi is an activity punctuated with fear- fear of mugging or fear of harassment, so we look down and walk fast- it’s about getting from one place to the other as quickly as we can with our phones still in our pockets and our lives safe.

What stops women from walking on the streets over here?

Well, the men!

Sorry. That was a stupid question.

No – it’s not a stupid question at all. It’s something I’ve often found myself wondering too – why don’t I walk out on Karachi streets the way I could in Bangalore? I think it’s because it’s so rare for women to be seen in the streets, when we do step out, it becomes a matter of public space and dominance. I feel that a lot of men catcall and harass as an attempt to exert their dominance over women – they do it because they feel they can. I only experienced one incident of eve-teasing in Bangalore, and I was so taken aback that instead of expressing anger, I only said, “Oh, harassment.”

You just said we share the same history, because India and Pakistan were once one country. Did you see this connection in the people, in the culture?

Definitely. We spoke to our hosts and discovered we had all grown up watching the same TV shows and Bollywood movies, that we had similar kinds of ghost stories and ate a lot of the same food. We had similar relationships with our families and cities. It really was eye-opening, because we sometimes feel that whatever we do is in isolation, but it’s experiences like these that remind us of how similar we all are.

Have you been thinking of writing a poem about your experience? About India?

I’ve been thinking of writing a poem about Bangalore, but I’m not sure where to start.

You definitely have more experiences now to draw from. What about writing a kind of political poem – becoming a kind of activist. Can you imagine that?

I feel like I already am. I mean I write poetry about feminism, about street harassment, about body positivity. I honestly feel like I’m not informed enough to write a political poem just yet, but who knows? I’m not gonna write it off just yet.

Any story you would like to end with?

I think the best story we have from the trip is when we were crossing into Amritsar. So our departure from Pakistan was longer and more complicated than we expected. We had a flight to catch from Amritsar at 2 pm, and it was 1 when we emerged from the Indian arrivals office. We had to cross through all of Amritsar, get to airport, and catch our flight. If we missed it, we would be in big trouble because our visa was only valid for Bangalore, and no hotel in Amritsar would be able to host us. We get to the airport with all of ten minutes to spare, boarding time was officially over but we already had our boarding passes so the airline was expecting us. There were six of us in total, and only two of us had access to the e-ticket. So we stood by the airport gates, getting clearance for everyone and we rush towards the airline counter when we realize one of us is missing. After a frantic search for Asad, we discover that he can’t find his passport. I lost it, I started screaming right there and announced I would get on that plane without him. After much searching and panic we finally found the passport – in the cab driver’s pocket – how it got there we have yet to discover.

Well, I would talk to the cab driver. Thank you so much for the interview.