“Feeling Otaku” – Interview with Didier Volckaert by Jian Tan Klein

Jian Tan Klein: Hi, Didier. You had a fascinating poster presentation on Otaku Culture at this year’s Asian Conference on Media, Communication and Film in Kobe, and I instantly had the idea to do an interview with you about it – especially as there are quite a few anime fans in my home country Pakistan. But before we get into that – how do you like Kobe? And what would be your favorite Japanese city?

Didier: I enjoyed Kobe. It has a nice feel to it. But I’m mostly attracted to bigger cities like Tokyo and Osaka. If I had to choose it would be Tokyo. I always visit Tokyo tower – perfect height, unlike Sky tree – to get a good feel of the city, especially as the sun goes down and the lights go on. It’s as close to Blade Runner as you can get (laughs).

So tell us about yourself a little please – what drew you to Otaku Culture? When did that happen, at what point in your life? Was there any ‘trigger point’?

I wasn’t drawn to otaku culture, one day I just realized I feel otaku. I grew up with anime end of the seventies, early eighties. It was on French television all the time. Harlock, Grendizer, Gatchaman … even though I had no idea this was Japanese, as it was dubbed in French, I immediately could feel this was different, more intense, more visual – just better. I started collecting toys in 1986 when I was in art school. I went to film school some years later where I discovered another passion: Experimental – or whatever – Cinema.

You are an artist and filmmaker, but you also call yourself ‘an otaku’. So you lack social skills, empathy, and self-awareness … I guess I’m an otaku, too!

Maybe, who knows? Do you watch hentai all day, too (laughs)? No, these are just some of the many stereotypes about otaku. Most of them are a result of sensational media coverage and a political-economical agenda to isolate these useless ‘drop-outs’ and blame them for everything that went wrong in Japan during the nineties. But we are extremely self aware, that’s why I guess we didn’t fight back. Otaku know that they don’t have the best of social skills, and our empathy is towards anime – or other pop/sub-cultural simulacra – and those who are part of the tribe.

‘Otaku’, I always thought it’s just a term for a ‘manga nerd’. Of course nerds are by definition not the most socially competent people – but in ‘the West’, they have gained a certain status as some crazy experts …

In contrast to Japanese otaku, the foreign ones are proud of their name and status as being ‘special’. Outside Japan it often means everybody who cosplays or watches a lot of anime or reads manga. Partly under this international influence the perception on otaku here in Japan shifted during the last decade – and some years ago the government started to exploit anime and its youth subcultures for their touristic potential. The クールジャパン – campaign …

Which means ‘Cool Japan’.

… exacxtly, so that campaign was an attempt to cash in on this soft power. It failed because of their inefficiency and lack of knowledge in this matter. Because of the reasons mentioned before, the term otaku has become extremely blurred. Today it’s also applied to mania, for instance to people who obsessively collect trains, or to militaria fanatics, to computer geeks – and I guess soon to everybody watching a movie twice. But to go back to answer the question, what ‘otaku’ is and who is ‘otaku’, that is extremely difficult to answer. So please accept this as my own perception on it: An otaku is an ero-centric being, he or she is voyeuristic and wants to share this.

So you’re social beings!

Yes, we are (laughs). It’s the origin of the term おたく. Otaku are focused on anime – not just the art, but the experience – and in this, we display autistic behavior. Anime has become a database of simulacra, a toolbox for our identity. To the otaku, anime is life itself, more beautiful and layered than reality, the fiction shared most widely. Not as an escape, not because we cannot distinguish fiction from reality, but because we consider it to be more effective. Therefor otaku are able to question identity, sexuality and even start relationships with imaginary, with 2D/3D life forms. This is the next step in otaku culture. Otaku and anime are creating new life, animated life, entities that manifest themselves. We otaku are already experimenting in how we will live together with these new life forms. We are visual anthropologists!

For you, Otaku is not a Japanese, but a global phenomenon …

Otaku are like anime itself, placeless and suspended in time. Anime was born in Japan, but it is not Japanese. It’s a child of different cultures, of European ‘mecha‘ – pre-Cinema and its apparatus to create the illusion of transformation -, of American Animation – Disney! -, and Tezuka’s own genius to turn the limited animation technique into a more emotionally focused art instead of an action driven, and finally of Japanese art and its Asian perspective, what Takashi Murakami calls ‘superflat’. This makes anime a unique mix and this can be experienced in any anime. Besides this you can also see it in the characters and backgrounds. These worlds and fantasies are not Japanese; they only exist in anime.

You even call otaku culture an avant-garde. What do you mean by that, what is so avant-garde about that avant-garde?

It offers strategies to cope with – and survive! – the current state of postmodern myopic. It’s like good Science Fiction, it can help you understand todays challenges and in the meantime it already offers a range of possibilities for the future – for the futures. Like William Gibson said: They – the Japanese – have been living in the future now for such a long time. That future will be AI and our relationship towards it, or she or he. We have to be aware not to repeat the mistakes of the past, slavery and colonization. That is why the erotic – and not just the sexual – aspect of otaku culture is so important. Love is the most human of everybody’s abilities and it needs to be the basis for our relationships with these new life forms. Not power, not robotica laws.

Today world and image have become the same and otaku are the specialists in understanding and working with images. We don’t have problems with what is real or not, with fake news and social media. This is why for example I do not consider a hikikomori to be an otaku. We clearly distinguish our liminal fantasyscape and the sensorial scape of nature.

Fantasyscape?

That’s a term I like very much, it was first used by Susan Napier in 2007 in her book From Impressionism to Anime. So in that way we are closer to Crusoe than to Quixote! With the last one we share the passion. We are amongst the few to be able to really participate in our hyper postmodern society. We co-create it, each in our own way, from the otaku sharing his love for his waifu on forums to the doujinshi mangaka expanding a franchise into other settings to the kigurumi performing his life to artists like Aida Makoto or Anno Hideaki working within otaku culture.

So you are kind of the opposite of the consumer-stereotype. You are also creators – and that is what is so interesting about your research: you are doing it as an artist. So you don’t come up with hypotheses so much and end with conclusions, but with … images.

Yes, that’s what I do. Work with prints, installations, books.

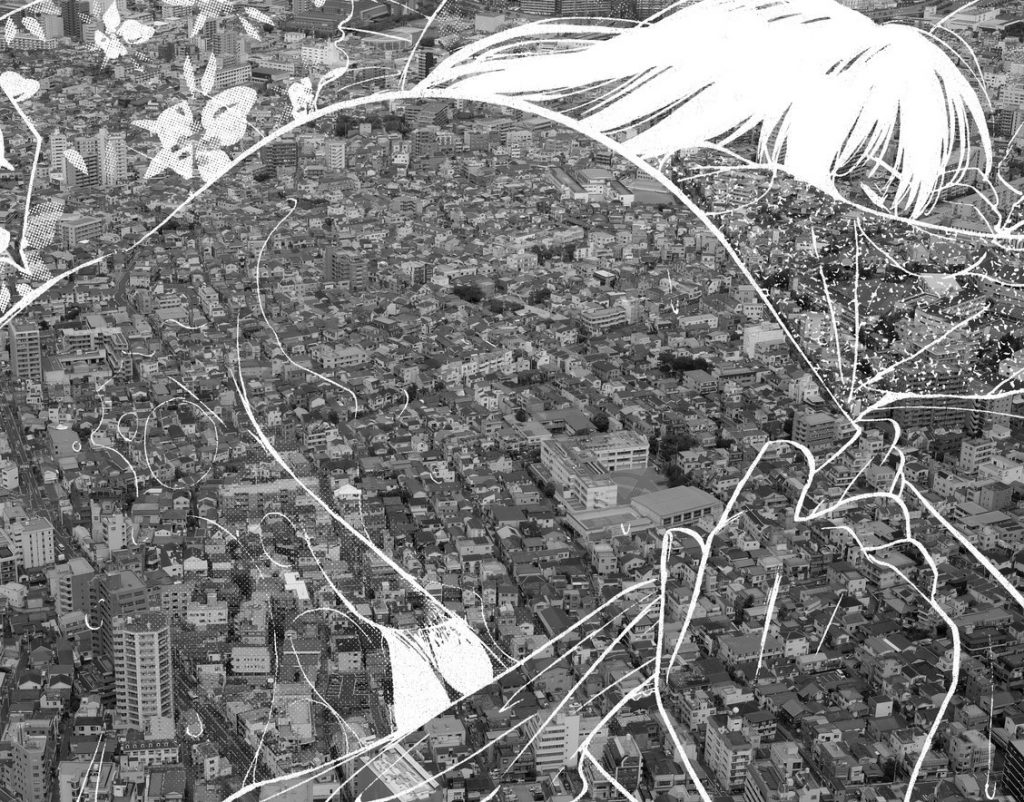

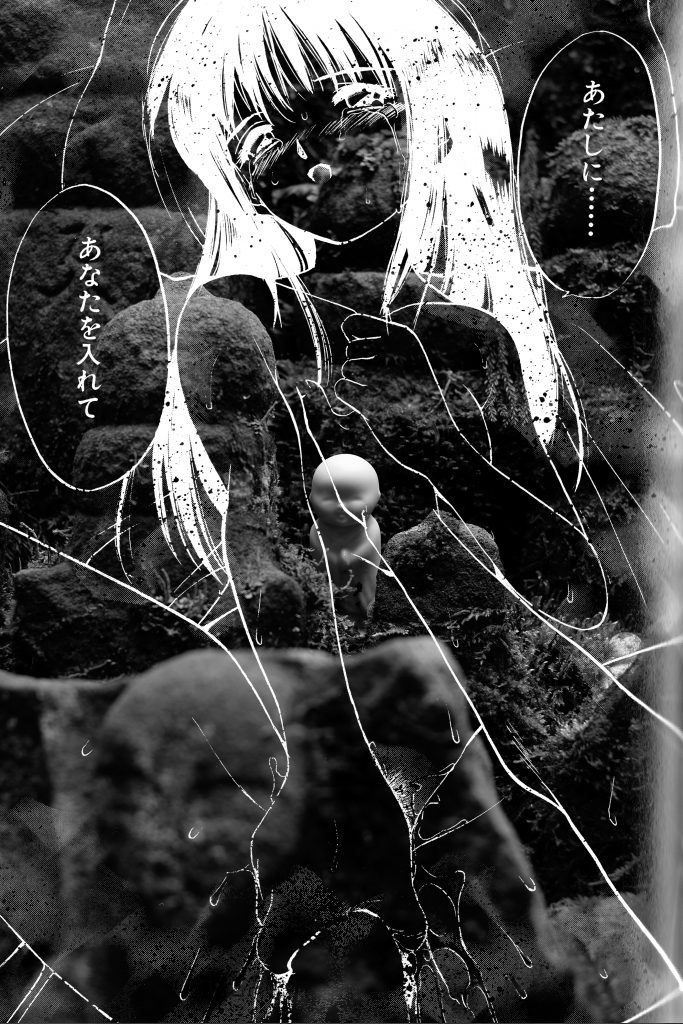

One of your projects is called The Invention of Crusoe. What is it all about?

The Invention of Crusoe combines original text fragments of Daniel Defoe’s 1719 novel with screenshots of the 1995 anime series 新世紀エヴァンゲリオン (Neon Genesis Evangelion), personal photographs and found footage. And the basic idea is to offer a glimpse of how to experience reality as just another fiction. As another way to build identity – to live, to love, to survive.

The story seems to be that Crusoe finds himself shipwrecked on this island and then turns it into an otaku paradise …

Yes, that’s how it starts. But he then realizes that his fantasyscape needs to be shared. For otherwise he has no real proof that he’s still alive. So one day, a young man washes ashore on Crusoe’s island and they become lovers. And they come to the conclusion that their world needs the ability to procreate, to expand beyond their imagination. When Crusoe finds out there are others – cannibals – on the shore of their island, he decides to rescue one of their victims, a beautiful young girl. So it is a kind of ménage à trois, a shared voyeurism between the characters, the reader and Ellis, the author. A perpetual moment of play that turns a diary into a picture novel that is as good as reality can be.

At the poster presentation, you said that you belong to an ‘older generation of anime fans/otaku’. What would you say is the difference between this older generation – and the new one?

I’m otaku second generation– from mid 70ties, the golden era – that was able to make the transition to the 3rd, starting with Neon Genesis Evangelion. To explain all the differences, even schisms, between the two generations would be a long answer. Also, I don’t know if there is a 4th generation yet. It has become so complex. But basically the big difference was 萌え (Moe).

Any future developments in Otaku you find remarkable?

‘Hatsune miku‘ has been a very exciting evolution I think, a break thru and a real eye opener for many non-otaku. And some months ago there was an otaku who posted in tears on 2chan that his waifu had made clear to him she wanted to end their relationship. This is the first recorded break-up in a human–character relationship from the side of the 2D! He got a lot of support and that was beautiful. I hope he gets to know another love soon.

Interview: Jian Tan Klein, images: Didier Volckaert

Find more of Didier’s work here: http://www.meta-bo.club

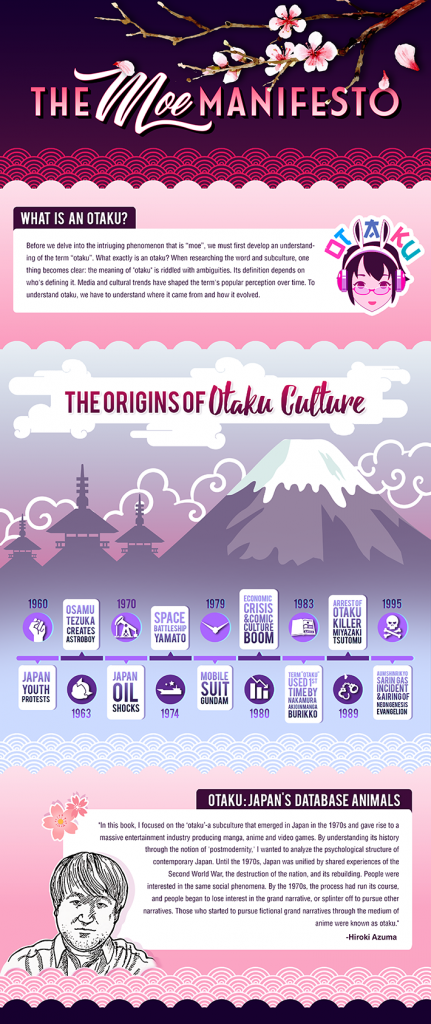

PS: For those of you who are into graphics, I’m adding one on otaku by the no. 1 otaku of Pakistan, Rida Rais: