Virtual Classroom: “Chinese and Western Values” – Q & A with Karl-Heinz Pohl

This is the first episode of our new series ‘Virtual Classroom’. It consists of a Q & A between Karl-Heinz Pohl, author of a text on “Chinese and Western values”, and 21 students from Xiamen University Malaysia, who have been carefully studying it – most of them from mainland China. The exchange between writer and readers took place in written form as part of the class on “International Communication” in the Journalism Department of XMUM in October 2019. S.J.

—

Q: Wu Qianyou

1. Is the Chinese tradition (eg. Confucianism) indeed similar with Buddhism?

2. Is Universalism universal to all of people and government around the world?

3. Is the West-centric theory still the mainstream thought in the “West”?

A: K-H Pohl

- Generally speaking, they are very different, but there are also a few similarities, i.e. in the way the “self” is downplayed (Confucianism: overcoming of selfishness, not self-realization, but self-transcendence, cultivation of oneself from a small, egocentric self to a large, all-encompassing self. Buddhism: the recognition of the fictitiousness, the illusion of the self is, in fact, enlightenment). Buddhism exerted a great influence on Neo-Confucianism (beginning in the 11th century). Most of the great Neo-Confucians started out as Buddhists.

- Universalism is an ideology, maintaining basically that we are all equal and the same (which is of course true, to a certain extent: we all have to eat, want to have sex, need to sleep and work etc), but downplaying the role of culture (Cliffort Geertz: The essence of human beings is that they are all culturally different. That is their common feature.).

- I am afraid, it still is.

Q: Cao Zhipeng

You say in your text that we should be open to other cultures and learn about them. Fair enough. Does it mean that the world culture will be unified in the future? Will many countries gradually lose their own traditional culture?

A: K-H Pohl

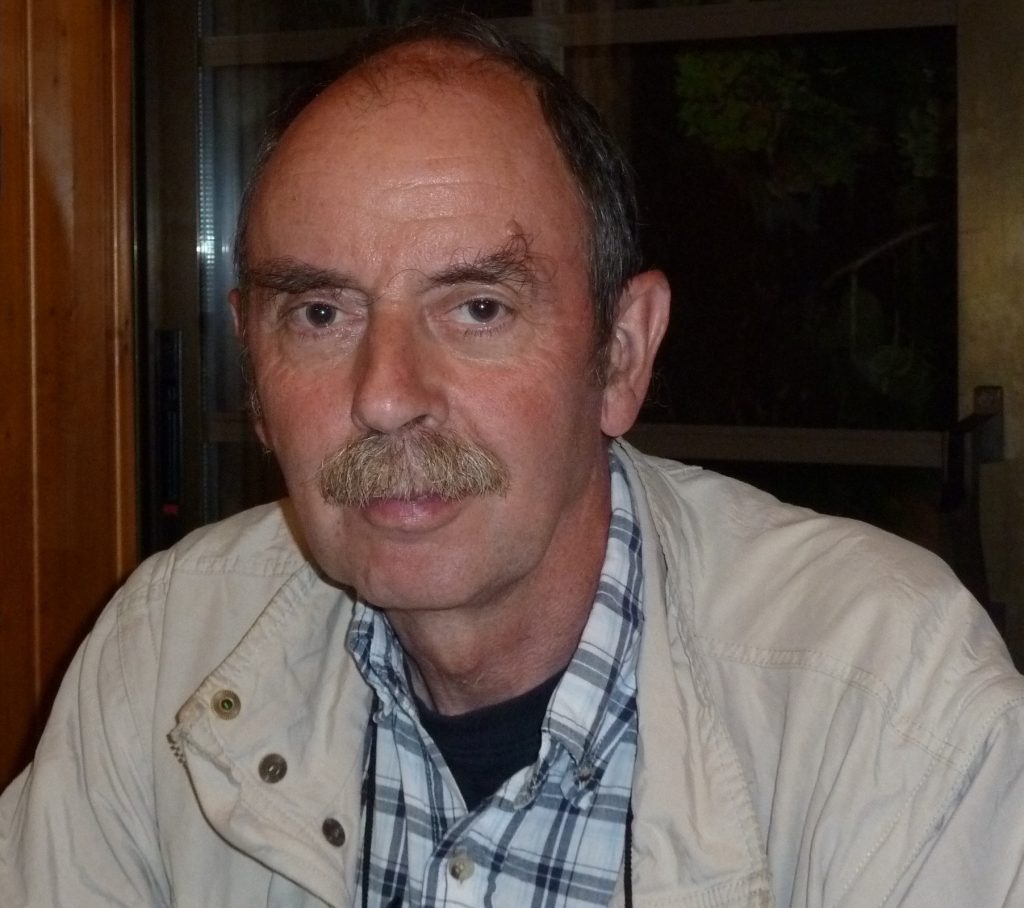

Karl-Heinz Pohl, Professor emeritus of Sinology from Trier University. Fields of research: Chinese History of Ideas; Literature and Literary Theory; Ethics and Aesthetics of Modern and Pre-Modern China; Intercultural Communication and Dialogue between China and the West. Selected publications: Aesthetics and Literary Theory in China – From Tradition to Modernity, 2006 (in German and Chinese translation: 卜松山,中国的美学和文学理论,2010). 卜松山: 发现中国 – 传统与现代 (Discovering China), 2016 (Chinese translation of China for Beginners – in German: China für Anfänger, 2008). Editor of: Chinese Thought in a Global Context: A Dialogue Between Chinese and Western Philosophical Approaches, 1999, and (with Anselm W. Müller) Chinese Ethics in a Global Context. Moral Bases of Contemporary Societies, 2002.

This could possibly happen. Some people want it this way: the American melting-pot on a global scale. Others emphasize “multiple modernities”. The strong influence of Western culture is certainly there; but on the recipient side, it gets always embedded in different settings (such as Chinese, Japanese, Indian …).

Q: Qian Weiming

China’s “One Belt, One Road” strategy is mainly focusing on the developing countries. Therefore, in the process of economic trade, the Chinese culture and development mode was also spread. However, they can only impact those countries which still need to perfect their own social system. For Western countries, which have been in the capitalist system for a long time, it is hard to accept a new ideology and they think some Eastern culture can’t adapt to their systems. How can they apply Chinese culture, also fresh concepts, to their economic and social development?

A: K-H Pohl

I don’t think there is an impact of Chinese thought in the West – possibly only Taoism to some philosophers or people with esoteric inclinations … The West has been on the top of the world order for a long time. Maybe the further rise of the Chinese model will create an impact. But we’ll have to see …

Q: Kong Xueying

To begin with, from your opinion, the Western value system and morality are secularized from their religion, and you think cultures can take references from each other, which I agree with. Meanwhile, I took issue with a few points: Firstly, you said that in the East, “the different schools do not compete with one another, nor do they try to oust each other; they tolerate one another and thus form a syncretistic unity.” Actually, just as the Protestant Reformation in Europe 16th century, different schools in China also fight with each other along the history. Violence is not rare thing. For example, Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor in China, he set Legalism as a ruling ideology while destroying Confucianism by burying the scholars and books, according to the official history books. Numerous scholars also died for their faith in eastern history. Secondly, Confucianism is basically not a religion, but a philosophy, since the subjects on which the Master did not talk, were: extraordinary things, feats of strength, disorder, and spiritual beings, according to analects of Confucius.

And how Confucianism works in China is not in a religious way, it is through politics. One of the most important reasons why Confucianism is so important is that it was once used as the standard to select officers by the emperor. Therefore, Confucianism is the main subject taught in various institutes in ancient times. The Chinese youth studies Confucianism to gain political power, respect and a higher position in society. Thus, politics and education make Confucianism more powerful than a value system or morality.

This reminds me of the current issue, the Hong Kong protests. Most of the protesters are the young people who were born around or after the independence of Hong Kong, who were exposed to the British education and ruling system, which seldom talks about the history and value in Chinese traditional culture. In their value system, democracy, individualism, freedom and equality are deeply planted into their mind and they consider Western culture as their identity. Therefore, I think the Hong Kong protests also reveal the differences between different cultures.

Although values of different culture varies, there are still a lot of common concept people can agree with such as the pursuit of truth kindness and human right, as we can see there are a lot of things in common in human’s history. Therefore, I think understanding and agreement can exist in international communication, and that is also what communication base on.

A: K-H Pohl

I agree with most of the points you made. But maybe you misunderstood some of mine. Let me clarify: Yes, 2200 years ago, Qin Shi Huang Di tried to crush Confucianism, had the scholars burned to death and installed Legalism as political philosophy. But according to my view, that was a rare case of ideological intolerance in Chinese history. The way I see it, Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism never struggled with one another the way European religions fought throughout history. Often, Chinese scholars combined elements of Confucian, Taoist and Buddhist thought in their life and daily conduct.

Yes, I agree, Confucianism is not a religion, but a social ethics, a moral philosophy, a way of ordering human relationships and the world. But as it is also a moral teaching, it has functional equivalents with Western religion (Christendom). Mind you, not too long ago (i.e. in my youth), Westerners learned morality through the teachings of the church. So the role of Confucianism cannot be so easily defined to the realm of politics – it is a mixed back.

Maybe you don’t know that, but in Indonesia, Confucianism is recognized and practiced as a religion by the overseas Chinese; they pray to “Heaven” – tian – as God. And not to Confucius.

I very much like the way you explain the problems in Hong Kong! Very well put!

Q: Liao Yuxin

My question is: Why does an uncritical ethnocentrism treat cultural manifestations as “mere superficial phenomena” and neglects their foundation in the history of ideas?

A: K-H Pohl

My formulation might indeed be a little shaky, particularly the word “superficial” which has a double meaning. What I mean to say is that crude ethnocentrists don’t ask questions about historical origins of cultural phenomena. For them, cultural phenomena exist just on the surface as manifestations of culture (not to be questioned).

Q: Choong Kam Poh

As you wrote in your text, people in China are in favour of stability due to the influences of Confucianism. There are also countries where similar elements from both Western and Chinese value systems are co-existed. Likewise in Malaysia, to some extent, Confucianism affects us and leads us to pursue stability. In the meantime, we do also believe in democracy and human rights. Because of that, it has long been an issue for third world countries on whether democracy does lead to a better society. Hence, do you think that the idea of democracy and freedom does work in countries where we have a co-existence of two different value systems? And why do some struggle so hard to combine the two?

A: K-H Pohl

Good question. I don’t have the ultimate answer. It just depends on a lot of factors and circumstances. Sometimes democracy and freedom work in such countries, sometimes not (Iraq, Egypt etc.). Mind you, the pursuit of democracy and freedom can sometimes also camouflage imperialist interests, such as with the US. Think about the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan or Vietnam …

Q: Wang Jingyi

You say: “We have to be aware of different stages of development between the ‘West’ and the ‘rest’ of the world (e.g., in the implementation of basic rights). The consequence of this assessment is not a cultural relativism but a historical relativism.” About this part, does the implementation of basic rights refer to the political aspect? Why is the consequence of this assessment not a cultural relativism? How to define this assessment between cultural and historical relativism? On Western culture-equal/individual Chinese-status-oriented/family, you state: “It is also common to view inconsistencies in the other culture as logical mistakes instead of accepting them as natural ambivalence (or being aware of contradictory phenomena within one’s own culture).” It is unavoidable that there exist inconsistencies in cultures, but how to explain natural ambivalence? What if the inconsistencies do influence the understanding of tculture? How should we see these inconsistencies as natural ambivalence if they are complicated combining with different aspects?

A: K-H Pohl

The difference between cultural and historical relativism is basically like this: Cultural relativism refers to different cultural backgrounds, arguing, for example in Muslim countries, that certain “universal” (that is: “Western”) values do not work or are not applicable there. Historical relativism accepts these “universal” standards but argues that the stage of development has not yet been reached to implement these ideas. After all, “universal” values have not existed in the “West” ever since the beginning, but have slowly evolved. Think about that racial integration (a “universal” value) in the US, which has only been achieved since the 1970s.

As to “inconsistencies” and “ambivalences”, let me again take the USA as an example. The US is apparently the standard bearer of the idea of human rights. But the US also injures human rights all the time with its neo-imperialist politics. After all, waging war against a country (without consent of the UN security council) with 100.000s of civilian casualties (the Iraq war) is certainly a violation of the human rights of the people that died in that war. On top of it, the US has the death penalty. According to European standards, this is unacceptable with the idea of human rights. The US, in fact, would not qualify to become a member of the European Union because of this. This is what I mean with “inconsistencies” and “ambivalences”.

Q: Xu Xiaoyang

1. What is the conflict between Chinese and Western cultural values?

2. Why can’t students’ acceptance of a teacher’s point of view be called intercultural dialogue? In many cases, teachers and students also communicate with each other on an equal footing and understand each other, to gain knowledge or opinions in the end.

3. Why can the core value system of culture be described as rooted in traditional religions?

4. In the article, you mention that different schools of thought in China do not fight with each other or exclude each other, but tolerate each other. How did this come about? Because in Chinese history, many schools of thought also had rejection and struggle.

5,What is this ‘equality’ pursued by Western society?

A: K-H Pohl

“Western” values – which have by now (rightly or wrongly so) become so-called “universal” values – derive from a certain cultural background or tradition, and that is Christianity. Because of the age of Enlightenment, Christian values have become secularized and are not easily recognized as deriving from this origin anymore; that’s why they are called “post-Christian” values. Chinese values basically derive from its long Confucian background (but also with Taoist and Buddhist influences). Since the May Fourth movement (1919), Confucianism is not considered the backbone of Chinese thought anymore, is often rejected. But because of this, people don’t see its long lasting influence. That’s why we can call Chinese values “post-Confucian” values.

Of course, teachers and students can have a dialogue with one another. But teachers teach students, and students learn from teachers. When we transfer the teacher-student relationship into the cross-cultural sphere, who is the teacher, and who is the student? Is the “West” the natural born teacher? And the “rest” always the student?

How the inclusiveness of the different schools of Chinese thought came about, is a difficult question. In China the different schools of thought certainly did not claim to have the absolute truth: Chinese scholars often combined Confucian, Taoist and Buddhist thought. There was also not an institution like the church with its power (such as the inquisition) that crushed anybody who held different beliefs. Also the relationship between religious and political power (Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire) is quite different from the Chinese experience. See also the exclusivist approach in Arabic Islamic culture – in contrast to the Chinese.

Equality is one of the 3 core values of the French Revolution. But it is more an equality before the law, not a Communist (or Maoist) equality.

Q: Zhang Chenwei

Why does the dichotomy not apply in the era when multiculturalism and anti-essentialism ideology prevail?

A: K-H Pohl

In the postmodern discourse of multiculturalism and anti-essentialism, people like to stress that one cannot make any generalizations about anything anymore, particularly not about culture, such as belonging to a certain culture. Each individual is, according to that train of thought, different and unique and does not fit into any (cultural or other) framework. They like to argue from a universalist point of view, stressing that we are all the same. If you argue from a cultural perspective in this environment, you are not on the political correct side: Because culture means: “difference”. They prefer to point out “sameness”, though.

Q: Wei Hongshan

- Why do religious beliefs become the foundation of social thought? Even now, religious culture is still the source of thoughts and behaviors.

- Why do eastern and western cultures export differently? Why did the west choose to be so violent?

A: K-H Pohl

I don’t know how that came about; I just see that that’s the way it happened. Particularly, though, in the Christian West and the Islamic tradition: Because they hold absolutist or exclusivist views.

I don’t know how the West became so aggressive or violent. Maybe it has something to do with early cultural exchange and territorial fights around the Mediterranean. Maybe it’s just the genes of European people/tribes … ?? I don’t know.

Q: Yang Xueqing

As Immanuel Wallerstein says, scientism has led to a separation of the true from the good in the social sciences and we’re facing the social fallout, of the waning of solidarity and the rise of social anomie, the break-up of families … apart from the problem of their grounding in Eurocentric presuppositions. So I’m wondering that, according to the current trend, will there be such a day that the world has an active learning from the east, where in their value system, social harmony and stability are given top priority?

A: K-H Pohl

I hope that there will be such a day. I think there would be a lot that the West could learn from the East.

Q: Lau Jing Pin

I found your article pretty comprehensive and thought provoking, so much that I cannot really nitpick any issues with the accuracy of the facts presented.

However, one issue that I have noticed from the first page of the article is that you made a statement where you claim that in order to notice any similarities between two vastly different cultures, both must be stripped to their most superficial level, or as you put it: “simplified”.

This statement does make sense. However, my concern is, if one were to look at the stereotypes or simplified characteristics of a certain culture, wouldn’t it be easy to wrongly assume things? Could this potentially lead to findings that are not entirely accurate and/or biased?

A: K-H Pohl

I agree with you. There is always a problem with gross generalizations. On the other hand, in daily life you can’t do without generalizing and simplifying. One has to be aware of its limitations, though. How do you handle statistical findings that tell you that for example 60 or 70 % of a certain group of people have such and such inclinations? Will you dismiss statistics, because it’s generalizing … ?

Q: Song Linxiao

- What does the “ritualized politeness” in The Dialogue between Civilizations: Methodological Considerations mean?

- At the end of Search for common concepts (trans-cultural universals), you say the universals should not lead us to find logical mistakes or contradictions between tradition (or ideal) and reality in the other culture. Is there any suggestion on what shall we do about their different impact on societies?

Allow me a remark: you are very neutral and unbiased. As a Chinese, I think I’ve learned how Chinese social values (the universals) developed, for which I want to express my thanks to you. I agree, there will always be debates in human/social sciences and there’re no absolute answer to the truth. What we need to practice depends on the development status, the philosophy of a society, issues in the world, history and even geography and climate.

Here’s a paragraph of Ambassador Chas W. Freeman, Jr.’s The Sino-American Split and its Consequences that I want to share: “It probably is also an advantage for China that, unlike the United States or the late, unlamented USSR, it is not ideologically messianic. Chinese do not seem to give a hoot how foreigners govern themselves, though they are, of course, flattered if non-Chinese seek to emulate them. China is for autocracy at home. Propagandistic assertions by American ideologues notwithstanding, it does not push autocracy or oppose democracy abroad.”

You do have a deep understanding of Chinese values. But the understanding rests on a traditional basis. China nowadays is changing fast. People begin to scan their faces to pay instead of QR codes. Food delivery is fast and convenient with usual discounts. There’s not much to worry about while hanging out at night. By the way, night market food is appealing. Majorities and minorities like the horde get along with each other. For me, I like the stability very much.

A: K-H Pohl

Thank you very much for your comments. The Freeman quote I find most interesting. Have immediately copied it. I fully agree with you, first what the huge population of China is concerned, second regarding the changes lately particularly in the younger generation. We’ll have to see how this further develops.

Regarding “ritualized politeness”, the point is that Chinese politeness is much more elaborate and rooted in traditional thought about right ritual behaviour. After all, the root of the modern Chinese word for politeness (limao 礼貌) is li – ritual, etiquette but which has ethical implications. For this reason, in the Chinese context, you cannot be over-polite. More politeness is always good, but not so in the West …

Q: Wang Feiyan

You say that “It is also common to view inconsistencies in the other culture as logical mistakes instead of accepting them as natural ambivalence (or being aware of contradictory phenomena within one’s own culture)”. So how can we separate the things which are natural ambivalence or are logical mistakes? Is this sentence saying there is no logistic mistakes in other country’s culture? And how to understand “people easy to fall into the similar trap” especially in “language learning”?

A: K-H Pohl

What I want to say is that there are always inconsistencies in life – therefore also in attitudes of people or, generalizing, in cultures. I advocate to just give room to inconsistencies (as natural ambivalences of which our daily lives are full of) – rather than to criticize them as logical mistakes.

The similarity trap can be observed in languages that are similar (like English and German), but still different. You see words that almost look the same, and so you assume it has the same meaning in the other language, but it doesn’t. This phenomenon exists regarding the usage of characters in Chinese and Japanese: They often look the same, but the way the Japanese use some Chinese charters is different from the Chinese usage.

I transfer the similarity trap to culture: We have politeness in the East and in the West. But Chinese politeness is different than Western politeness.

Q: Gao Yiqie

1. Page 5: mention that difference historical experience may influence intercultural dialogue , and when in dialogue, they may neglect other foundation in the history of ideas. Whether there is a causal relationship between the two?

2. Page 8 : whats the difference between “reciprocity” and “natural or positive law”?

A: K-H Pohl

Reciprocity is just “tit for tat” (Chinese shu 恕). Natural law is a concept that developed in the West during medieval times from Christian roots, saying basically, that we have an inner compass (given by God) of what is right or wrong. Similarly to Confucian ideas of an inborn goodness (liangzhi 良知). Positive law is the concept that all legal codes are set by man – and can change over time, because people during different times – and culture – will have other priorities. Seen from this view, “natural law” is something metaphysical …

Transcript: MH & SJ

Pohl, K.-H. (2013). Chinese and Western Values. Age of Globalization 3: 35-43.