“Images work in different layers” – Interview with Andy Spyra by Arqam Khan

Hey Andy, how are you?

I’m fine, thanks.

So how do you like Pakistan? “Pretty fucked-up”?

What? (laughs)

That’s what the heroine in “Zero Dark Thirty” says when somebody asks her that question.

So I guess I shouldn’t mention India here (laughs). I have been kicked out of two countries already, I don’t want Pakistan to be the third one. Honestly, I can’t say much about Pakistan, I have been to Karachi for four days now and everything I did was jump from one place to the next. To get in touch with a city, you need to walk down the street and I haven’t done much walking, I have been teaching this workshop on photography here for the past few days. But what I like about Karachi is that there are so many things happening at the same time. I cant say much about the people actually, because with people you need to interact with them, and I haven’t been able to really do that. But Karachi has been one of the most intense places I have been to so far. It overwhelmes your perception – all these sounds and sights and smells…

We’ve seen a bit of your work that you have done in Kashmir. Can you tell us a little bit about the political restrictions that are in place? How many laws did you have to break to take the pictures that you have ?

I never asked their permission, so actually I don’t want to know how many laws I broke. You know, I just work with the people. So like on a local level, I work with people that witness what is going on in Kashmir. It’s difficult to talk about Kashmir in particular, I try to stay out of the politics of that region now. Remember, I have been kicked out of India.

And out of Turkey!

Well, they didn’t let me in, that’s different (laughs).

It’s perfectly okay if you don’t want to talk about it.

We can totally talk about Afghanistan and Kabul, because especially with Kashmir it can be trouble for me later on. So I can talk about it in general, you know. Working in conflict zones in general is very similar, most conflict zones share the same aspects. You usually stay under the radar. Or you work with some of the official people.

What happens if you arrive at such a conflict zone, what are your first steps to – well, to familiarize with the conflict?

Ras al Ayn, Syria – 11.10.2013: Scene at the frontline in Ras al Ayn, where the YPG is fighting the al Nusra Front / ISIS.

I just came back from Nigeria, it is one of the most difficult places to work in. People are suspicious of the photographers, and with the government it’s always edgy because you never know what you are allowed to do and what could be a problem. Ruthless insurgency of the Boko Haram is significant, so first of all you work with a fixer and you work with a local guide, you meet someone who tells you: ‘Okay, you can stay here for this long’, and so you will be in many situations in which you get out maybe for just ten minutes, you take a few photographs of the market for example and then you get back in the car, because otherwise you would run the risk of getting kidnapped. Or there would be a bomb attack which would be specialized to public places, because they are volatile spots for suicide bombing. They happen very often in the area. So the more tense the area is, the more complicated it is to work there. You have very little time to work, you have to be very precise in these very unfortunate circumstances likewise. You can’t always pick to work in the best spot, you have to work with what you have in front of you. So you spend most of the time trying to organize things, taking permission or trying to dodge them. The actual shooting is maybe just ten percent of the time. Most of the time you get caught up with the logistics coming to places, getting out of places, and the shooting is always a very small part, and it always has to be quick, quick, quick. You never really have time to spend time shooting outside.

Did you ever have a near death experience trying to get a photograph?

In Afghanistan I didn’t cover the war, in Afghanistan I covered the people of Maazar Sharif. Mazaar Sharif is a good place to work in. The more you work in an area with a conflict, the more you realize that you can’t generalize the word ‘conflict’ or apply that category of conflict to the whole country. Pakistan, if you look at it from Germany’s perspective, people think there is bombing, there is kidnapping, there is a war going on in the north … But if you’re here in Karachi, it’s all fine, you know. The same in Iran, you go to one place, everything is good, but in half an hour you could be on the frontline, there is shooting going on and they are fighting against Isis. So half an hour or twenty five kilometers is the distance between the frontline and you having a cappuccino with your friends. What you learn in these environments is that you measure security in kilometers rather than in country borders or city borders. I don’t think you can call Pakistan or any other area a war zone, it all depends on where you are, what you are doing, how you move around. When you’re there you get a feeling of how an area feels like. And a feeling of the neighborhood, it changes from neighborhood to neighborhood – in one street it’s totally fine, and in the other street there would be a madness or violence going on. In Kashmir it was clear that every friday people would go to Jammiah Masjid and then there would be the friday prayers and after friday prayers there would be a protest and some people would die every week. After having been there for like six weeks, I asked myself: Okay, do I really want to go to the friday prayers again? I have a child at home, so it really becomes your decision. One shouldn’t become cynical, but it’s just the reality on the ground, and in one street you have a massive protest going on and in the next street people are sitting and having their Chai. People get used to it. The human being is amazing in its ability to adjust to these circumstances. How quickly people adjust to war! And how they get by and how they survive with that …

So one could say you’re more interested in the ‘zone’ than in the ‘crisis’? Is this why you became a ‘crisis zone photographer’?

Yes, I think that’s true. I’m interested in conflict, but not only in taking pictures of some shooting going on. That is not my main objective of going there, for me it’s much more about what does the conflict do to the people, what are the underlying causes that lead to the conflict, what’s happening after the conflict? I also want to record the aftermath of the war, what it does to people and whole societies. But why I became interested in this … I guess because war in my culture was something rather alien. We were one of the generations in Germany that grew up completely without any armed conflicts, even the Cold War was over when I grew up into a conscious mind. So I got interested in that because it’s completely alien to me, so I started traveling to areas of conflict to … well, actually the first time I experienced conflict was by chance. I happened to be in India and I was travelling around and I ended up in Kashmir by chance. I stayed there overnight and then woke up the next morning and there was some shouting in front of my hotel going on. So I went outside and there were all these people shouting, and there was tear gas in the middle of the road. I don’t know how it all started actually, but I was like sucked into the situation. That’s when I became interested in the bigger questions surrounding such a collective form of aggression, like what does it do to the people.

You see yourself as someone who informs others with his pictures, a news reporter with a camera. On the other hand your pictures are not just documenting what is going on, they have this aesthetic quality – they are beautiful…

As they should be.

Oh, so this is about morality? Seriously, don’t you see a conflict right there?

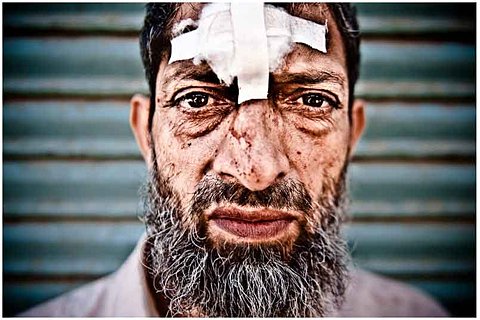

I know what you’re trying to get at. But no, I don’t see conflict here. I don’t feel any paradox. The job of a photographer is to make photos of the things that are happening, whatever there is, whether it’s a cup of coffee or a body, to me it’s all the same. And part of that job is to make things look beautiful, because only through true beauty communication works. If my picture is ugly, nobody would want to look at it. So I try to make it as beautiful as I can. Even if it’s a dead body or a mother that just lost her son, I will take a photo in such a setting so that people look at it. I draw the line when I feel the dignity of the person I am photographing or the dead body or something is humiliated. That’s the red line for me. That’s where I stop.

Alok, Al Hasakah, Syria – 11.10.2013: A dead body of a fighter of the Jhabat al nusra can still be seen days after he has been killed in the fighting between the YPG and his own unit.

I looked at two of your pictures, they both had the same motif. One was in black and white, it was beautiful, but it was also transcending the situation, and one in color, it was much more ‘real’. In the end, blood is red, not black or grey.

It’s very much a personal choice. I believe images work in different layers, they have different composites and elements. So one ingredient is light, another one is composition, and another ingredient would be color. It all comes down to this. If you look at the image, all these subconscious processes in your brain will distribute that, how much you like of what. And color is just adding another layer to it. I am working in a bigger context and I am working with trauma and genocide, so I want to take pictures which transcend the actual moment and color takes away your attention from the light. Different kinds of photographers perceive reality in their own way, and visuality for me is very much about light and composition. When I look through the view finder I focus on light and composition. In my images you can see that this is it for me. Other photographers have a really good sense of color, they know where to place color in their pictures, I don’t do that, for me when I have color in my images, very often I find it just distracting. Because my senses don’t really catch the colors and it’s disturbing for me, and it also takes away the attention of the audience from what I am trying to say.

As a Gora who travels to such places, you definitely have a different perspective, so how do your subjects respond to that? Are you ever concerned about your photographs being exploitative?

I am not sure if I am distinguished by my race or the color of my skin if I am for example working in the Middle East. Having worked there for quite some time now, I can say that it’s not that bad. But in Nigeria, I am of course totally alien by my skin color, by my culture, by everything really. I even feel like an alien myself there, too. But I don’t think skin color has to come in the way of your work, I think what comes in the way is cultural unawareness, or not being educated enough, not being smart enough to understand the circumstances. When I went to Afghanistan for example, what I shot there was very much from a white man’s perspective. But in the Middle East, after a few years, it’s a little better. I understand the culture much better, so now people understand my personal perspective, my personal view towards things, even though my background is very different. There is a discussion going on now about female photojournalists and why we have so few female voices, and not just that, we also have very few black people, if you look at professional photojournalists, eighty five percent of them are male, white and middle class…

Just like the typical serial killer.

Exactly (laughs). If I go to any conflict zone, these journalists will look like me, and they will come from the same background, which is very concerning because a lot of voices are missing. It’s not my fault, I picked to do this profession, but I think these voices are missing in the visual discourse about war. They could add interesting insights to many situations. Which is one reason why I came here to teach a workshop for Pakistani photographers. I find this really important. I have been doing this all over the world now, because I think it’s important that these voices are heard. A Pakistani can tell stories that I can never tell, because she or he knows the language, the culture, and they have the access to people that I will never have. But all that really distinguishes me from them is that perhaps I am more experienced in the field, and that I had the privilege growing up in Germany and going to a good photo school. Life as a photographer is very hard in Pakistan, actually in most countries of the world, but it’s also a big chance in times of crisis, economic crisis, to make their voices heard and to add their point of view to the story.

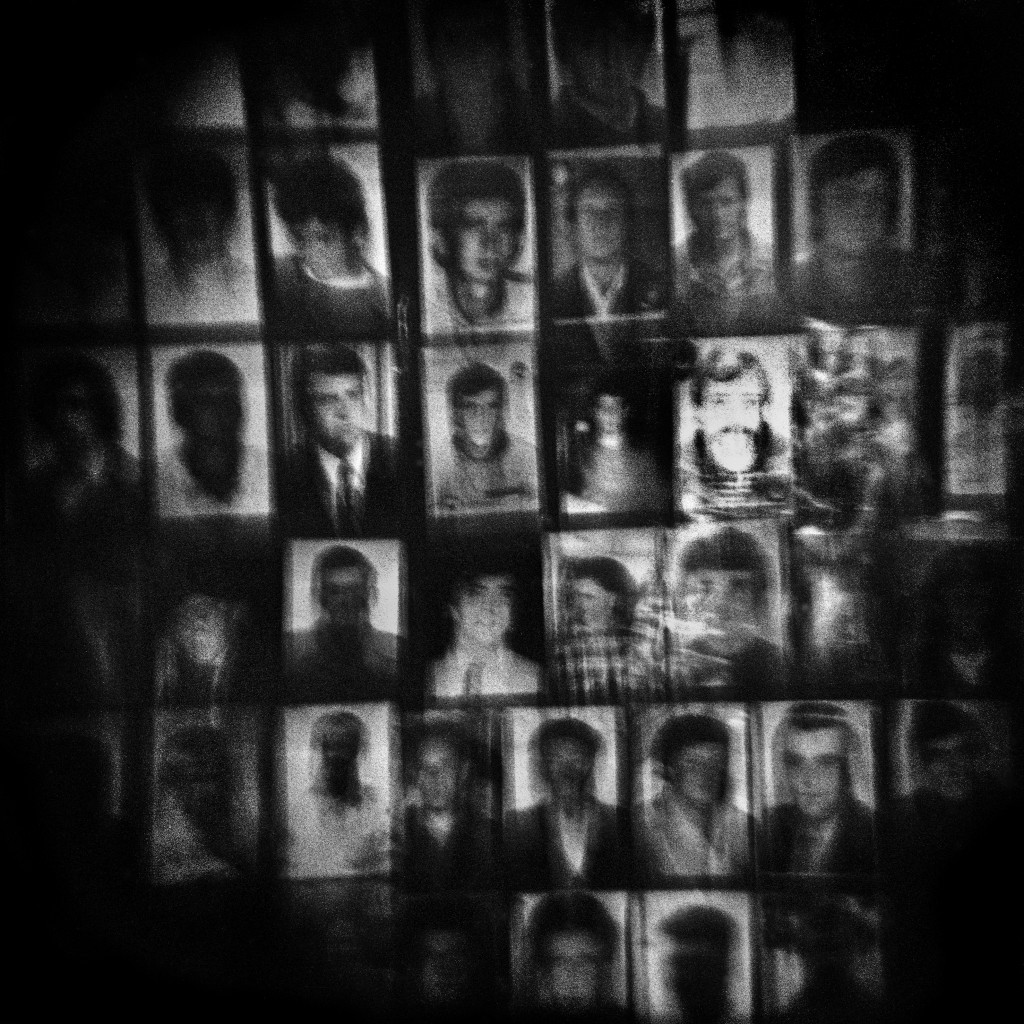

The images of missing persons from Srebrenicacan be seen on a placard of the organization ‘Mothers of Srebrenica’ during their monthly rally in Tuzla.

And what about you being exploitative?

No, I don’t feel I am being exploitative. I go to a war zone and I see all this shit happening … Of course it’s my job, I am making money off of it, but that’s not the point. I go to these areas because I think there is something happening that I utterly dislike, and I feel like it’s my privilege and my duty to show this to the world. My project in Nigeria is very much about Boko Haram insurgency. I know it’s an old topic, it’s one part of the wider piece of the picture of what’s happening in Nigeria now, but now no one really goes there anymore, because it’s expensive and it’s inaccessible and you need time to work there. What is happening in Nigeria will effect Europe, too, the influx of weapons and the outflow of refugees, and it will have adverse consequences for the south of Europe. I think it’s very important for someone new to go there and tell these stories. And if there are no local people doing that, then it’s my duty and privilege to go there and tell these stories as a journalist.

Let’s talk about some formalities. What goes into your post editing process, and what medium do you prefer, analogue or digital?

On average it’s like one to two minutes per photo. It’s mostly about what I can do in a dark room, doing and burning the areas of the image. Or maybe more, if I want to I will photoshop the image to enhance what you already see, like the light or a certain mood. About my favorite medium, I am pretty much working fifty-fifty between digital and analogue. It really depends on the project and the camera whether I prefer film or digital.

So what’s next?

First I am going back to Germany, I am going to see my little kid, gonna see my dog, and then the next thing is probably Somali land where I am doing a story on ex-pirates who have now become fishermen.

Good luck, don’t get shot – and keep us posted please.