“My only trick: to be as Austrian as possible” – Virtual Classroom session with Bernhard Zand (Der Spiegel)

Dynamic, passionate, experienced, humorous: Bernhard Zand in motion, screenshots: M. Heidingsfelder

In this new episode of our virtual classroom series, students of UIC’s 2021 “Entertainment Journalism” class talk to Bernhard Zand – long time DER SPIEGEL correspondent, linguistic miracle (who effortlessly switches between several languages in a single sentence), passionate jogger, and last but not least: Austrian.

ZHANG Lian: How can political journalism be entertaining?

(laughs) Good question, very good question. Let me answer from the heart. It can be entertaining when you have interesting people to write about. When you find protagonists for your report which interest you yourself. And, most importantly, when what you write about has some contradictions.

I always find that my work has to be entertaining, too. Generally, when you as a journalist feel that when you research a story, you are surprised, you are shocked, you are amused, you scratch your head because you don’t understand something, then usually the report that you produce provokes the same reactions with your readers. That makes the things entertaining.

So again, to make political journalism entertaining, it is important to speak to people who are entertaining, who are either interesting or amusing or shocking or – in any way – move your own mind forward. When you learn something. That is most important! Imagine, I’m in my mid-fifties, and what I still enjoy most about my job is, I always want to meet someone who’s world and who’s life I haven’t met before. Every day that I don’t meet somebody who tells me something new, who surprises me, who brings me forward, I think is a lost day for a political journalist. This is obviously a constant process of learning.

Anything is allowed that is not boring. So, when you start the story, when you start to report – that’s my experience at least – try to challenge yourself, try not only to find the protagonist for something that you already have in your mind and you just look for people who can exemplify what you want to write anyway. But dare to go for the contradictions, dare to surprise yourself, and your report will be entertaining or interesting for the reader as well.

Bella: As journalists in China, we are sometimes confronted with certain political demands. How to find a good balance between entertainment and ideology?

I’m not sure whether I feel Ied by ideology. Frankly, I’m a very unideological guy. Whenever I have a feeling that ideology seeps into my story, or even into my own thinking, I get very critical.

Maybe I can answer your question with an example. As your teacher Markus may have told you, I used to stay in the Middle East before I came to the Far East, meaning, to China. I remember that whenever I had the feeling that a thought of myself about the Middle East became to clear, when I noticed that my reporting was repetitive, and specifically, when it developed a sense of bias, when I noticed that my stories always take the same direction, I became very self-critical and by my own decision I decided – so to say – to go another way. If I could not do this because the news situation was very clear, when we had – I don’t know – a specific angle which dominated the news for a long time, then I deliberately tried to choose another subject.

I think as journalists we do have quite some leverage, even within our news organizations. It may be a little more difficult in one organization than in another, in one country than in another, but generally as journalists, we always have the freedom of choice what kind of reports we do. As I said, whenever I feel that … ideology is really harsh word, I think it is a little too tough for a Western journalist to use that particular expression. Maybe there are media which consider themselves ideological. But let’s say when you recognize that reporting is going in one direction, when you become one-sided, then I think as individual journalists we should try to step back and, you know, just do a sports story once in a while. Or do a story about archeology. Just change the subject. It’s a bit like in private life, when you recognize that you’ve become too concentrated on one thing, almost too obsessed with one thing, it’s always a good idea to step back and sort of re-arrange your interests and your focus – that will always give you a chance to get out of a certain way of thinking.

DENG Qi: Where do you get your ideas from? What inspires you? Is there any methodical way to come up with stories?

I think it is about fifty-fifty, it has been for many years now. One half of it is dominated by the actual agenda, by things that are simply happening. When I wake up in the morning and I go through my news, I can usually already tell: “Oh wow, that will dominate the day”, and of course you can never completely ignore this as a journalist.

Bernhard Zand has worked at the German news magazine DER SPIEGEL since 1998. He was a correspondent in Istanbul, Cairo, and Dubai, and deputy head of the foreign desk. He has reported as Middle East correspondent on the wars in Iraq, Gaza and Lebanon. In 2012, when Xi Jinping took office as the head of the Communist Party, Zand became DER SPIEGEL’s correspondent in Beijing. Since November 2021, Zand is based in Hong Kong. Before leaving the country next year, he traveled all across the nation and reported on how the Chinese people are faring today. His summary: “China has risen to become a world power for the second time in recent decades, an unprecedented comeback. One reason is China’s sheer size, its vastness, its density and the deep roots of its culture. The other, which is even more important, is the diligence, creativity and patience of its people.” Photo: DER SPIEGEL

But! These of course are so to say the obligatory stories, the reports that you have to do anyway. You still can be creative with these. I think my challenge always is to – even in the most routine subject … what were the news today? Ah yes, for example that the Americans have declared a diplomatic boycott to the Olympic games – of course, I’m sure, I’ll have to produce something about this somehow today, I don’t know in which format or which channel – but because I have seven hours time difference to my editors in Germany, I already wrecked my brains: How can I tell this a little different? Is there an aspect that I could bring in that probably other news editors, other journalists may not think about. So I’m really thinking about how to write a slightly different and a more informed report about this. But still, this is basically everyday work that all of us have to do and where half of our ideas come from.

The much more interesting of course half of our work is when I see something – and for that I, how should I say, I try to stay a little like a child. You know, I have been based in Hong Kong for the past year or so. It was a little difficult, because it’s only one city, I’m used to travel a lot and get inspirations from all kinds of issues. But to give you a recent example, where ideas come from that I enjoy much more than the daily news mill, so to say. I’m reading the newspapers here every day. One newspaper is called The Hong Kong Standard, and on their first two, three pages, they always have these huge advertisements. And I noticed when I came across it for the second or third time that they are offering something strange here, which is called: “A Cruise To Nowhere”. So you go on a cruise ship, you just circle around basically the Hong Kong islands, and then you come back.

It took me a few days of reading these advertisements until I realized: This is probably an interesting story to report on. It has nothing to do with the daily news grinding I described before. So I called up Hamburg and said: “You know what, I’ve read these advertisements – what do you think, should I do such a cruise myself? Get on board, try to speak to the people?” Somehow, I intuitively knew that this is going to be an interesting subject. This comes with many years of working in journalism.

Bernhard Zand’s article on the US boycott of the Olympic games was published shortly after this interview. Translation: US government boycott of the Olympics: Not being there is everything. Joe Biden largely stands by Donald Trump’s China policy. Now the US president has announced that he will not travel to the Winter Games in Beijing – and is looking for imitators.

So again, half of what we do – roughly, ok? – comes from the daily events that you cannot escape. And there I think the challenge for a reporter, for a journalist is to still try to bring an aspect to these stories that is interesting. As of the diplomatic boycott for example, I thought: It’s about 50 years now that ‘Ping Pong diplomacy’, wàijiāo (乒乓外交), started. And I find this is an interesting aspect, probably most of my colleagues will not think of this fact – it is an interesting contradiction that this time … When ‘Ping Pong diplomacy’ started 50 years ago, it really came from the sports people; this time, the politicians, the diplomats are making diplomacy a little slower. So it’s a contradictory development if you understand what I mean.

In this ‘news mill’, you try to find a new aspect within an already given frame, given through the current situation; and other than that, anything goes. You just have to have an open eye, walk through life like a child, and whatever you tell your own family, you know, may be relevant. When I do a video conference with my daughters back home, what I am telling them about my life here is usually a good idea for a journalistic story.

ZHAO Wanru: Do you think a journalist should be a specialist? For instance, if I want to work for a financial newspaper, should I major in economy?

Ha! That is a great question. And economy is exactly the subject on which I’d like to answer this – because I am not an economist. But I think, generally – and whenever my economic desk calls me to write about something, or when I have an idea – I’m always, even in my mid-fifties, always very self-conscious, I’m always worried, I think: “Oh my god, I don’t know all these terms!” I’m not an expert in how exactly central banks come up with their rates and all that, but I have my experience. And I did financial stories, starting as a rookie reporter in Turkey, when I had no idea about finance and economy at all! But I think my readers actually liked my financial or economic stories. You know, I studied philosophy and literature – not even in my private life am I good in handling my finances. So I think what you should do if you have to work about any subject – not just economy: medicine, sports, culture – and you feel that you do not have the professional education for that subject: make a point of it! Usually, namely, your reader or your viewer or whoever is consuming what you present him, is not an expert either. So I found it an advantage to work about subjects in which I’m not a professional.

Zand’s article on Zhao Tingyang. Translation: Zhao Tingyang is one of the most important thinkers in China. He considers the world in its present form to have failed and predicts a new order. Is that propaganda?

Having said that, it is of course very, very good to know about subjects as well. And I think it can give you confidence as a journalist. As I said before about where the ideas come from, I would sort of make it a fifty-fifty solution. It is good to stand with one leg in a field where you really have sureness of stand and where you feel a confidence. As I said, I studied philosophy and literature, and in fact I have written about philosophy. I wrote about a Chinese philosopher for instance, Zhao Tingyang, maybe you have heard about him, he is famous for his work on the concept of the tiānxià (天下). It was a good experience for me to write about this, because I knew that I know more about this subject than most of my editors do, so personally it gave me confidence, but since journalism is mostly about being interested in something, about being – what is the best word here – nosy about something – “I want to know what is going on here, I want to learn this myself!” – I think generally it is often better to write about something you don’t know so much about yourself.

Maybe one last example if I may. I came to China in 2012, and I came from the Middle East. Neither did I speak good Chinese, nor did I have a big understanding of China. But a very experienced colleague of mine in Hamburg where I came from, told me: “Oh, it’s a good idea that you go to China, because you are like an undeveloped photo.”

You know in the old days, when you developed photos on paper, you had to go to the dark room, and the paper was white, and the latent image on that paper then became the visible negative or positive by chemical amplification of that image. That’s me when I came to China, I came to China as a white sheet of paper, as a latent image, if you like, and everything interested me. People interested me, the agriculture interested me, the infrastructure interested me … I was not an expert in anything, but I think by not being an expert I was closer to my readers then I would have been after twelve years in the Middle East where I considered myself sort of an expert.

So it’s always good to have one field of speciality, be it economics, be it medicine, be it sports, be it whatever subject – but being a generalist myself, I always find it more fulfilling to write and research about subjects where I am not an expert.

Edward: When we work for newspaper organizations, how do we find a balance between what we want to write and the newspaper’s agenda? Have you encountered something like this?

I wouldn’t say that I have encountered an agenda. That would be a little too much to say. Really, I mean I’m not in any way sugar-coating. Of course, every editorial room has a direction, and is trying to form an opinion on things that are happening.

I am just thinking of a good example which would help you with this. None comes to mind at the moment, but what I generally would say is: Just try to find an irresistible story. An irresistible person. An irresistible protagonist. Something that is so interesting that even an editor who might have a different opinion on a given subject cannot resist and realizes, this is something that he has to tell, because this is something he would tell his wife in the evening. Something that is so interesting you have to tell it to somebody.

Back in the days of the Iraq war, you may remember, the world was very divided at the time. The American government was dead set on invading Iraq, most of the European countries were dead set not to do that, and in Germany particularly, there was a feeling of: We are not going to do this. And I felt a little uncomfortable, I was in Baghdad at the time, I was against the Iraq war, because I knew the situation there, and I didn’t condone this. Not that this was difficult. I could have suggested many, many stories about why I thought it was a bad idea to invade Iraq, but I had done that with several reports before. And then I suggested a report about the race course, the horse race course in Baghdad. Believe it or not, in Iraq under Saddam Hussein, almost up to the day of the American invasion, they had horse races – like here in Hong Kong the Jockey Club, and I knew if I suggest this story, they cannot resist it. Because it’s just in itself too interesting.

Everybody would say: “What? Under Saddam? You have a horse race? Who goes there? How much money do they bet? Where do the horses come from?” And I knew I could relate some information from that very odd and very unpleasant place that I was in, in a very tense political situation, to grab my editors’ and my reader’s attention by just telling a story that is irresistible. And if you are in doubt what makes an irresistible story, think of what you tell your friends or what you post on Weixin, what you think is worth telling. It may sound very general, but I have found this to be true all through my journalistic life for sure.

Jessie: What is more important to be a good journalist – talent or hard work?

That is really hard to say. Obviously it is both. Sorry for referring to my age so often, but since I’ve been I this job now almost 30 years, I can tell you, the hard work never stops. It is not getting easier. Of course, there is something like experience, but whatever I do will only be good if I have to really struggle for it. Everything that you do not have to struggle for is usually not such a good product. Talent – I don’t think you have to worry about talent. If you didn’t have talent, you wouldn’t sit in this course in the first place. Talent is usually there, and if you don’t enjoy what you’re doing, you will not get into this anyway.

Aurora: Sometimes we want to interview some very famous people. Do you have some advice how to get in contact with them – and also how to behave when in the interview situation?

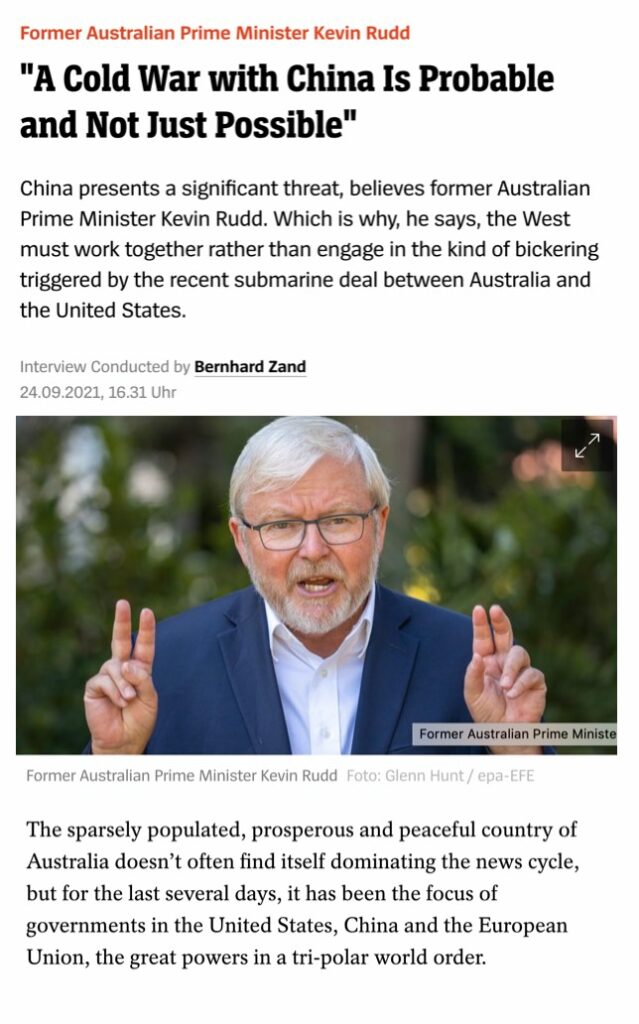

Well, to get somebody to talk to you of course is a messy thing. This will never end, and it can get frustrating. In fact, I’m trying to get somebody to agree for an interview right now, and I’m very frustrated because he – in this case it’s a man – he has not yet agreed to meet. But, to give another example, a few weeks ago, it was after the Australian submarine deal, you may remember, it was in September I think, immediately, I saw the news and I thought: Ah! I need to speak to Kevin Rudd, the former Australian Prime Minister. I knew it was the right time to speak to him, he was the right person to speak to – so how did I do this? I happen to know somebody from Australia, I asked him “Do you know somebody who might have a direct contact to him?” So I don’t have to go through the, you know, whatever – his office, or the Asian Society, where he is president, which makes it complicated and the steps are difficult … And in that case I was lucky.

Bernhard Zand’s interview with former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd

So in one case at the moment I’m very frustrated, because I don’t get the OK of that person – in that other case of Kevin Rudd, I wrote him an email on a Saturday morning, I thought, this is not really polite to address somebody on his private email on a weekend, but he immediately responded and I got the interview – on video, like right now.

Once you have succeeded to get to someone, the big challenge of course is: How to get somebody to talk? How to get somebody to tell you something interesting? Because people who you’d like to interview are often people who are used to giving interviews. They usually have their ‘talking points’, as we call it, in their mind, and of course, simply, in cognitive terms, it’s easier for them just to just give talking point after talking point, so they tend to tell the same thing all the time. I have no ‘One-size-fits-all’ solution to that. But I happen to be an Austrian. We Austrians are considered to be smooth when we’re talking – we establish this as a form of something enjoyable … That’s my only trick, really. To be ‘as Austrian as possible’.

I’ve always found the Chinese mainland is also … it’s interesting, in all the countries I’ve been, there are some ‘talking peoples’ – it’s of course very generalizing – but there are some countries where people just like to talk, and there are others where that is not the case. My general rule is, the Austrians like to talk – more so than the Germans, right, Markus? – the Egyptians like to talk, they are great talkers, it’s very easy to interview an Egyptian, and the mainland Chinese also – mostly – like to talk. More actually than the people in Hong Kong. At least that is my personal experience.

So – be talkative. I think if you’re not talkative and if you find it difficult to open up to somebody, maybe journalism is not a good job for you in the first place. These would be my two advices: You can never solve the problem of contacting somebody, and once you are in a conversation, try to be warm, open-minded, and interested.

Let me give you one final anecdote. You may know the former American president George W. Bush always found it hard to get in a personal contact in a conversation with former Chinese president Hu Jintao. I think they had three or four meetings, and Bush was always a little unhappy, saying, “We just don’t connect”, so for the fourth or fifth time, he really thought about what he is going to ask him. And he asked him: “President Hu, tell me, what keeps you awake at night? I can tell you what keeps me awake at night, it is how can I avoid another attack like 9/11. What keeps you awake at night?” And guess what, Hu Jintao gave a very interesting answer to that very simple question. He said: “What keeps me awake it night? How I can find 12 million jobs for the Chinese people next year.” You may find that sometimes these simple recipes work quite well even in journalism. Not only for politicians.

Video interview via Tencent, Zhuhai – Hong Kong, 30 November 2021. Recorded by Weinan Yuan, transcript: Deng Qi and Markus Heidingsfelder, webpage layout: Zhang Lian.